The Karakalpak Kiymeshek - Part 5

|

The Karakalpak Kiymeshek - Part 5

|

|

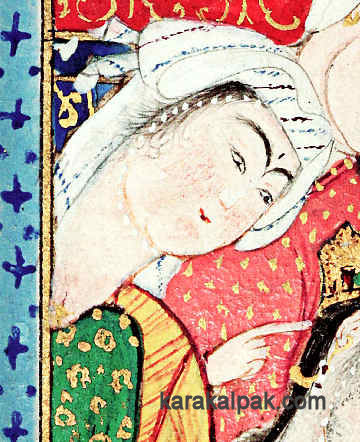

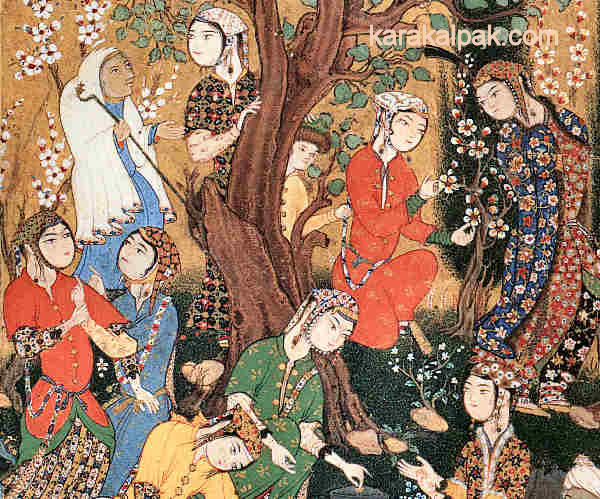

ContentsPart 1SummaryThe Karakalpak Kiymeshek Role of the Kiymeshek The Aq Kiymeshek The Qızıl Kiymeshek Part 2Different Qızıl Kiymeshek PatternsDistribution of Qızıl Kiymeshek Patterns The Dating of Qızıl Kiymesheks Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms References Part 3Other Kimeshek-Like GarmentsThe Qazaq Kimeshek The Uzbek Lyachek The Tajik Lachek and Kuluta The Turkmen Esgi, Lechek and Chember The Kyrgyz Elechek and Ileki The Khimar and Similar Islamic Veils References Part 4Previous Ideas on Kimeshek OriginsA Short History of Veiling up to the 16th Century References Part 5The History of the KimeshekWhere to see Karakalpak Kiymesheks References The History of the KimeshekIn 1990 Z. I. Rakhimova published her study of the evolution of Mawaran-nahr female fashions in the 16th to 17th centuries from the miniature paintings included in manuscripts held at the Saltykov-Shchedrin State Library, the Leningrad Division of the Institute of Oriental Studies and the Institute of Oriental Studies named after Beruni in Tashkent.Rakhimova concluded that girls braided their hair into two plaits, whereas women always concealed their hair. In Bukhara and Samarkand, in the first half of the 16th century, girls wore skullcaps and a shawl or rumol decorated with a peshonaband. The latter was a long and thin embroidered or bejewelled panel that was sewn to the front of a folded shawl to decorate the forehead, the shawl ends being twisted into a tape and then tied behind the head. Women also wore the peshonaband but with a chockkap, or kultapushak, a cap that included a rear plait cover. In the 17th century girls wore a pointed or dome-shaped embroidered cap on the front of the head, with an aigrette of long feathers fastened at the back. Women meanwhile wore a round cap with a shawl fastened at the back which wrapped around the sides of the head and the chin to hide the neck and upper arms, falling down at the back to the shoulder blades. In some cases this was translucent. Once again, an aigrette of feathers was fastened at the back. When it came to the headdresses of elderly women, Rakhimova found that they were quite different. These were formed from a folded rectangular shawl draped over the head with the two opposite corners tied under the chin and the two other corners freely hanging down the back and covering the upper arms. These shawls are depicted with a circular opening for the face. During the 17th century they were sometimes also worn over a peshonaband. Rakhimova added that: "A similar shawl, called a kimeshek (in Kyrgyz) or lyachak (in Uzbek) is depicted in the 17th century miniatures not only of Mawaran-nahr, but also of Herat, Tabriz, and Qazvineh, and probably, generally for the entire Middle East region."

Illustrations from Rakhimova. Upper left: Mawaran-nahr 1540s; upper right: Samarkand 17th century;

|

|

Another contemporary image shows a girl with a red cap surmounted by a white kerchief and a translucent veil wrapped under the chin and falling

down to her shoulders:

|

Many girls just wore a cap and a small kerchief, leaving their plaits fully exposed:

|

By the middle of the century the length of this head veil became longer at the back and the corners hanging down each side of the face were

sometimes pulled back to reveal long earrings, or temple decorations. Sometimes an additional small white veil was tied under the chin like a

kerchief, concealing the neck.

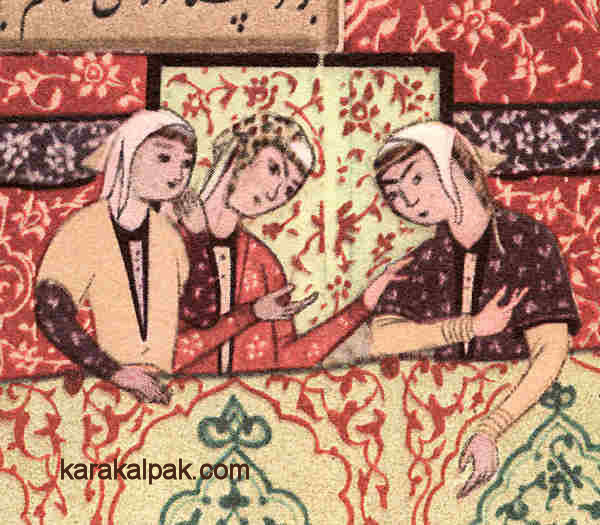

The costumes of the young women of Central Asia at this time were illustrated by the so-called Bukharan school of miniature painters, brought

from Khurasan and patronized by the Shaybani Uzbek Khans. Unmarried aristocratic women were shown wearing two types of headdress. In one there

is no head veil even though the women are shown in public, just a long ribbon is fastened in the hair and hanging down to the lower back, a style

that seems to have originated in pre-Safavid Herat. In the other the women wear tiara-like headdresses with an ornamented coloured kerchief,

folded in two and fastened at the back, exposing the ears, long earrings, and temple plaits:

|

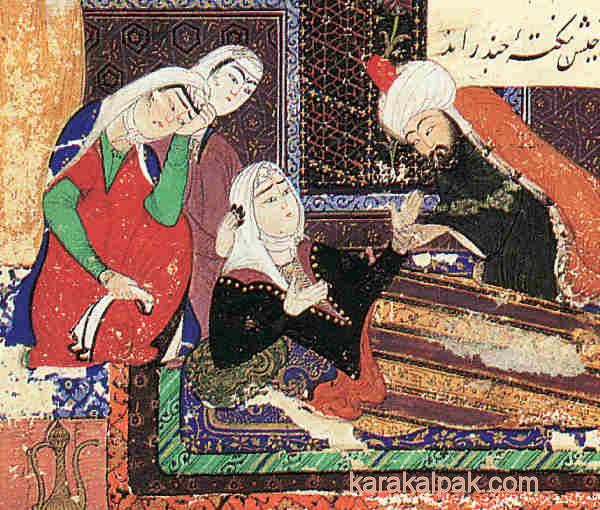

Other images show women, assumed to be married, wearing a cap covered with a larger diagonally folded kerchief, the two opposite corners falling

down towards the breast and the two aligned corners falling down the back to cover the hair:

|

Meanwhile older women appear to have forsaken the khimar-like head veil in place of a tailored kimeshek-like garment. However

the images need careful interpretation. The following detail shows an old woman facing a young woman in an open window, apparently wearing a

kimeshek-like headdress over a black cap. Yet she could equally be wearing a headscarf draped across the front of the neck, over the

head, with the free end concealed as it falls dawn the back:

|

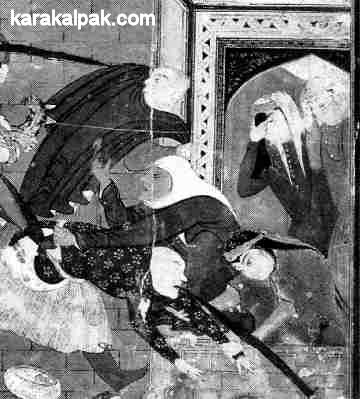

Likewise in the following detail of women under attack in Isfahan while one woman wears a cap and kerchief another wears a black head veil, tied

under the chin and held in place with a bandeau. However the old woman wears either an old style khimar-like head veil or possibly a

kimeshek. There is insufficient detail to make a decision:

|

A painting ascribed to Mir Sayyid 'Ali shows a nomadic encampment with several women, clearly married since one has a child on her knee. They

wear white head veils that completely cover the hair. An old woman enters Layla's camp with Majnun shackled with a chain. She wears a white

cowl over her cap, with detailing around the face opening and folds around the neck which show that this is a tailored kimeshek-like garment

and not a khimar-like shawl:

|

A second idealized painting of a nomadic campsite shows another old woman wearing a white kimeshek held in place with a bandeau, while

the younger women wear small head veils over their caps, one tied below the chin:

|

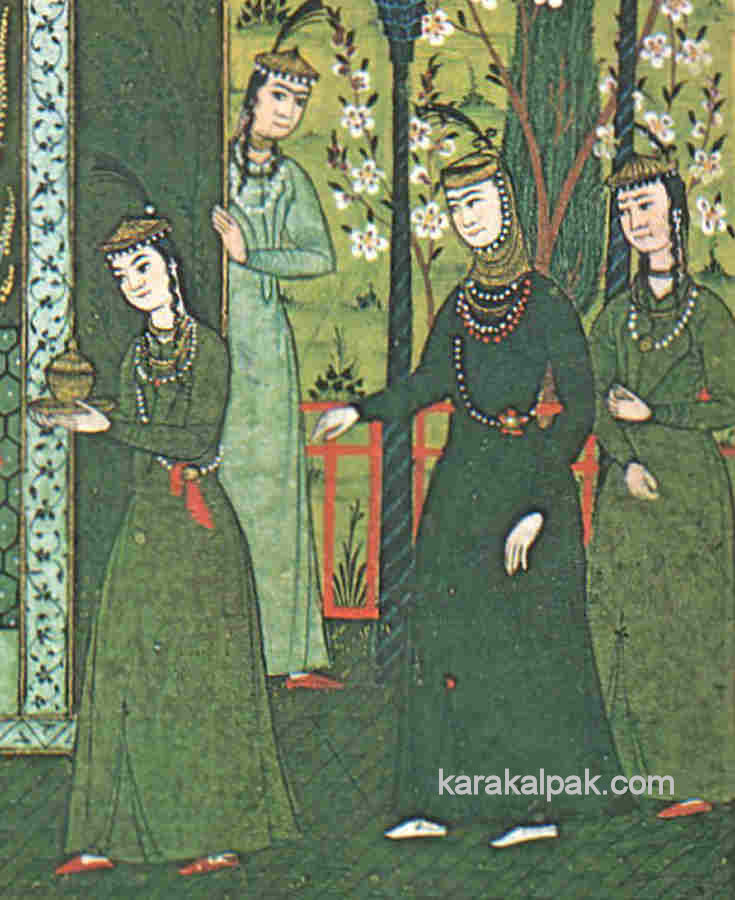

However we would be wrong to assume that the kimeshek was only confined to the old. The following slightly later illustration shows

a group of four women, two wearing head veils hanging down to the shoulder blades over a cap, and two wearing cowl-like garments over a cap.

The object of the painting is Haftad's daughter, a maiden who lives with her seven brothers in Gozaran. She is depicted in a purple cowl, which

is clearly a kimeshek because it has a line of decoration along the bottom at the front:

|

In the illustration of "the shoemaker who rode a lion" we are shown the headdresses of not only the shoemaker's wife, but also his mother-in-law.

The former wears a small kerchief below the chin and a larger kerchief tied with a bandeau over the head, concealing her hair. The latter wears

a large shawl, wrapped around the head with the tail hanging down to thigh height. In the same miniature two women look down on the scene from

a window. One of them, who appears to be neither a girl nor an old woman, wears a white kimeshek:

|

|

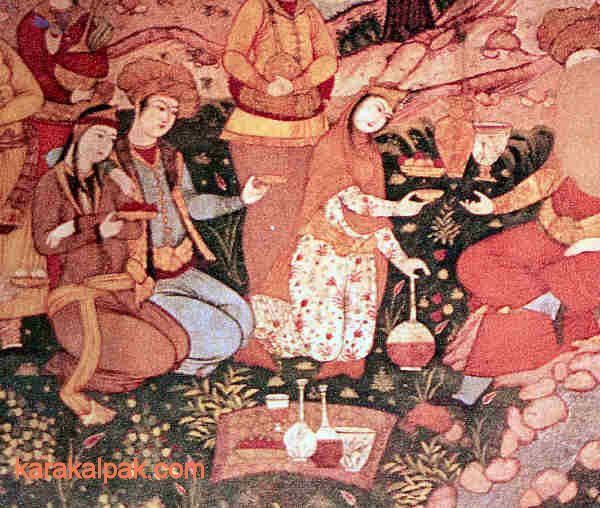

Another image of an old woman's headdress appears in the painting of a group of young aristocratic women preparing a picnic. All of the girls wear

colourful and ornate kerchiefs over their caps and some wear a second kerchief tied under the chin and colourful ribbons hanging down with their

plaits at the back of the head. Such headdresses are frequently depicted in miniatures painted by the Qazvin school. Of particular interest is

the hunchbacked old woman wearing a bukhnuq, somewhat similar to a modern chador:

|

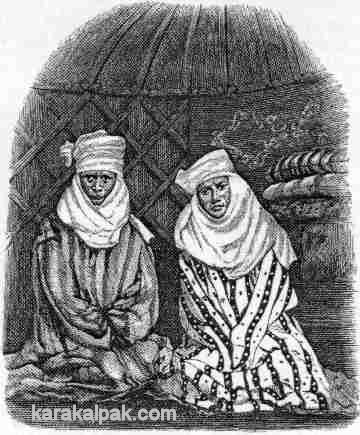

By the mid-17th century, there were strong cultural links between Central Asia and Mughal India. One of the fashions taken to India by the

Mughals seems to have been the kimeshek. A miniature painted in the Deccan shows two women wearing either khimar-like head

shawls or more likely kimesheks, judging by the patterning on the headdresses. The only caveat is that the latter could just be a

stylized form of painting:

|

Meanwhile a new style of headdress seems to have been in fashion in the new Safavid capital of Isfahan, depicted in wall paintings decorating

reception pavilions at the huge new royal residential quarter:

|

|

It appears to be a large cape-like kimeshek, worn below a diadem or headband, wrapped tightly around the sides of the head and below

the chin, falling across both arms to completely cover the chest down to the waist. In both images the rear tail falls down to reach the ground.

At about the same time in Central Asia and Khurasan we observe the emergence of a new style of costume, with tight-fitting dresses - possibly

influenced by the fashions of India ornately decorated takhiya or taqıya caps for girls and a new type of hair veil for

married aristocratic women. In the following detail of a Mawaran-nahr painting, Pari, the daughter of a Tatar chieftain, goes to meet

her husband Bahram Gur. She wears a flat-topped cap with her hair and neck entirely concealed under a cowl or wimple-like shawl. Her three

attendants wear taqıya-like caps with pointed tops and bejewelled sides and a plume of feathers rising from the back:

|

Such fashions remained popular for princesses and notables, townswomen, servants, and musicians at least until the final quarter of the 17th century.

At that time the only centre of miniature painting in Mawaran-nahr was at the kitab khana in Bukhara, the royal library of the

Ashtarkhanid dynasty. According to Galerkina, this ceased to function during the 1670s, eliminating a vital source of information for the

monitoring of costume changes during the 18th century.

Interestingly the miniatures studied by Rakhimova show the initial signs of the emergence of another new form of head veil in the 17th century

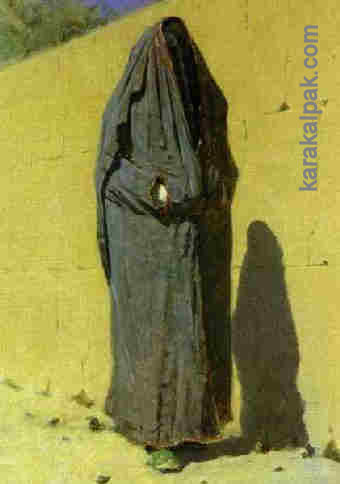

the ubiquitous paranja. When Baron Meyendorff was stationed in Bukhara in 1820 he recorded the public costume of the Uzbek and Tajik women:

"In the streets, the women wear a long mantle, whose arms join behind, and a black veil which hides their face completely; they see badly through this veil, but the majority raised a corner of it furtively, when they met one of us."Two years later Nikolay Muravyov wrote that the Uzbek women of Khiva: "... dress in a very strange costume and generally go about veiled". Married women were strictly segregated and according to Muravyov, "condemned to a life of strict solitude". In 1863 Vambery found that the crime of casting a look upon a thickly veiled lady in Khiva could lead to hanging. Henry Lansdell found it virtually impossible to come into contact with women in Bukhara and Samarkand in 1874. The all-encompassing paranja and the accompanying chachvon horse-hair face veil were now firmly established and would continue to be worn in public until the 1930s:

|

However Fedor Fedorov Grushin, who was captured by Turkmen off the coast of Mangishlaq in 1819 to be sold as a slave in Khiva, saw another side of

Uzbek female headwear:

"Female head-gear in Khiva somewhat resembles the kokoshniks of Kostroma [a town on the east bank of the Volga], or the earlier fashion of the grenadier cap. This attire is called "kabavy", and pearls and stones are set [in those of the] rich."Such headdresses are kept in the Ichan qala museum today, where they are described as a tax'ya duziy, and are somewhat similar to the Qazaq kasava. Grushin's comments warn us to differentiate between the Uzbek female costume that was worn in public and the headwear that was worn in private. It is likely that kimeshek-like cowls continued to be worn at home and under the paranja, although few Western travellers would have ever had the chance to see them. George Curzon commented in 1889 that he had never seen the features of a Bukharan woman between the ages of ten and fifty because they were always concealed behind the paranja and chachvon.

|

In 1767 the Berlin naturalist Peter Simon Pallas was invited to Saint Petersburg by Catherine II, just in time to lead the first of five major

scientific expeditions to Eastern Russia and Siberia planned over the coming few years. Pallas left in June 1768 and in the following year reached

the Qazaqs of the Lesser Horde pasturing on the North Caspian Steppe. Not only did he record the construction of the Qazaq turban-like headdress,

made from several white or multi-coloured cloths, but he arranged for it to be sketched and subsequently published as an etching. The completed

item was called a dshalot:

"First they put a corner cloth [diagonally folded square cloth] over the head, two to three ells long [1 ell = 1.135m], around which they wind their two hair plaits. They cross the corners of the cloth under the chin, and put them over the head again, so that the neck is covered in front, and also at the back by the hanging down corner of the cloth. Then they wind a similar folded strip of cloth, 4 to 5 ells long and in the middle nearly two hands broad, around the top of the head to form an almost cylindrical turban."

|

A second expedition left Saint Petersburg in the same year of 1768, heading for the Caspian, Orenburg, and Hungarian steppes. It was led by the

Swedish botanist Johann Peter Falk, who was assisted by Johann Gottlieb Georgi and Christoph Bardanes. In September 1770 they visited the Khan of

the Qazaq Lesser Horde on the Ural River near Orenburg. Falk's notes describe the costumes of both the common and the distinguished Qazaq woman.

The former wore a large cap with a kerchief tied under the chin. They then tied a large cloth known as a tashtar around the cap, which

hung down over the back of the shoulders falling towards the ground. It was decorated with braids, ribbons, and hanging pendants. From the rear

of the neck was suspended a set of cords decorated with tassels, ribbons, and "jingle-work". Higher-status women wore an elegant vest-like garment,

known as a ruster, which went over the head, covering the breast and the back down to the waist. It was decorated with corals or small

silver plates, as well as Bukharan gold and other coins. On their head they wore a tall decorated saukele-like cap with a long wide plait

cover hanging down the back to the calves. Fortunately both costumes were illustrated in Falk's published travelogue:

|

|

In the following year, Christoph Bardanes, who was a member of Falk's research team, travelled to the Jungar steppes for an audience with Sultan

Mamet, the leader of the Qazaq Middle Horde. The Sultan sat with his younger consort, who wore a silk scarf wrapped around her head "as is

common with the Tatars and Armenians" according to Bardanes.

The final account is provided by Johann Gottlieb Georgi, who maintained the expedition after Peter Falk's suicide in 1774. His ethnography,

published a couple of years later, provides another similar description of the Qazaq head veil:

"The veil is their daily headdress; to dress themselves up they put on bonnets covered with small medals etc., similar to the bonnets of the Bashkir women. Several of them, especially the women above the common run, cover the head with a type of tall turban and composed of some fabric, which they wrap several times around the head."His coloured engravings appear to be based on the same source used for Pallas's slightly earlier engraving:

|

|

The surprise is that Alexis de Levchine's monograph about the Qazaqs, based on his role as Russian administrator of the Qazaqs at Orenburg in

1821 and 1822, makes no mention of such head veils, although it does describe the Qazaq saukele. However such headdresses must have

still been popular. When the military topographer, Ivan Fedorovich Blaremburg, left Orenburg to visit the Qazaqs of the Inner Horde pasturing

between the Ural and the Volga, he took along headscarves as presents for the Qazaq women.

An illustration published in Germany in 1844 depicts a married Qazaq woman without the turban-like uramal. She wears a saukele

over what appears to be a kimeshek, although in the absence of any commentary it is impossible to be certain:

|

However just twenty years later we gain our first historical record of the kimeshek being worn by the Karakalpaks and perhaps a similar

garment being worn by the Qazaqs. The source is the Hungarian Orientalist Arminius Vambery who, in 1863, travelled from Persia to Khiva and onwards

to Bukhara disguised as a dervish. His original travelogue is silent on the matter but in his addendum, published in 1868, he noted that Qazaq

women wore a sheokele, which was more conical than the Turkmen headdress and "allows the veil to fall not before, but down the back of the

loins." They braided their hair into eight thin plaits, four on each side, and covered their heads with a letshek in cloth, which covered

the head and neck.

His comment on the Karakalpaks is equally concise:

"... the [Karakalpak] women have a cape like a cloak round the throat,"This cannot be a jegde and it is therefore most likely that Vambery is referring to the aq kiymeshek, since it is unlikely that the Karakalpaks had access to significant quantities of Russian woollen broadcloth (ushıga) at that time. Of course Russian textiles were being imported by Khivan merchants from Nizhniy Novgorod and Orenburg, but ushıga would have only been affordable to wealthier Karakalpaks as evidenced by its use on the tumaq of the 19th century sa'wkele. As Vambery was well aware, the Khanate of Khiva was a dangerous province for foreigners and no Russian merchant would dare to trade there directly. The majority of Karakalpaks were desperately poor, maintaining a self-sufficient subsistence economy. The primary textile was homewoven cotton bo'z and silk was readily available in the form of cocoons sold on the pilla bazaar at major markets such as Kunya Urgench, Qon'ırat and Shımbay.

|

|

The majority of travellers entering the Qazaq steppes in the years following Vambery's visit report head veils wound from lengths of cotton cloth.

Januarius MacGahan, on his journey from the Syr Darya to the Amu Darya east of the Aral Sea, referred to the "high white turban of all the Kirghiz

[Qazaq] married women", while Eugene Schuyler, who passed through the territories of the Qazaqs of the Lesser Horde beyond Orenburg in the same

year of 1873, commented:

"The women ... have their heads and necks swathed in loose folds of white cotton cloth, so as to make a sort of bib and turban at the same time."

|

In the summer of 1882 Henry Lansdell crossed the northern Qazaq steppes from Omsk to Kuldja (Yining) in Xingjian via Semipalatinsk, finally reaching

Vierny (modern Almaty). He noticed that while wealthy Qazaq women wore the tall saukele:

"The poor women swathe their heads with calico, forming a compound turban and bib; ..."Similar comments were made by Henrich Moser in the following year:

"What characterizes the costume of the married woman, who never shows her hair, is a large white scarf with which she surrounds the head, the bottom of the face and often the bust."

|

From their later ethnographic studies, Zakharova and Khodzhaeva have suggested that the Qazaq kimeshek had two initial forms. In the

western regions, corresponding to the territories of the Lesser Horde, it was a cowl that was pulled over the head, but in the eastern regions of

the Middle and Greater Hordes it was a length of cloth tied up under the chin. From the above observations this does not seem to have been the case.

The western Qazaqs of the Lesser Horde also used a length of cloth rather than a cowl in their 19th century headdresses.

In 1873 General von Kaufmann finally commanded the Russian invasion of Khiva, annexing right bank Khorezm and its Karakalpak population as the Amu

Darya Otdel and incorporating it into the Syr Darya Oblast of Turkestan. At last we get reports about the local Karakalpaks from

Russian officers who were part of the invasion force and by civilian advisors and visiting writers and artists. The remarkable thing is that none

of their reports from Maksud Alikhanov-Avarskiy, Leonid Sobolyev, Aleksander Vasilyevich Kaulbars, Herbert Wood, and Nikolay Karazin mention

much about their appearance and none mention the kiymeshek. Sobolyev came closest by noting that Karakalpak women hide there hair under

shawls. An anonymous Russian author, whose account of the Russian campaign was translated by Spalding, added that the Khivan Uzbek women wore long

conical turbans, made of from fifteen to twenty Russian cotton pocket-handkerchiefs.

There are probably several reasons for the lack of information on Karakalpak costume. Firstly the members of the initial Amu Darya expedition

entered the region from the Aral Sea and their first encounter was with the Karakalpak fishing communities in the northern delta. At the time of

the Russian conquest the Karakalpaks were generally poor and oppressed, having been worn down by heavy taxes, forced labour, and the deliberate

flooding of their lands. However the occupants of the northern delta were even poorer still. The Russian conquerors therefore initially encountered

the most depressed section of the Karakalpak nation. For example, Karazin described a Karakalpak woman "all in rags, dirty and barefooted".

Secondly, as was pointed out to Karazin by a local mullah, the faces of their women could not be seen by outside men. The women were also

shy and fearful of strangers, so they either ran away or were hidden from view. Thirdly, for the Karakalpaks the kiymeshek may not have

been an item of daily wear but a ceremonial costume, as it certainly was later on, only worn by newly-weds (or possibly first-time mothers) and at

festivals.

After the Russians pressurized the Khan into signing a favourable trade treaty their merchants soon arrived in Khorezm, establishing their main

trading centre at Urgench. Russian manufactures began to be imported into the region in growing quantities over the coming decades, especially

textiles such as plain cotton, coarse calico, striped tick, printed calicos, woollen cloth, silk, and brocade. Market research was conducted to

ensure that fabrics were selected to satisfy local tastes. One textile in particular struck a cord with Karakalpak women red and black woollen

broadcloth that had been machine-hammered so that the surface became felted, thereby concealing the warp and the weft.

Another highly desirable luxury textile was also being made locally in Khiva ikat-patterned adras. In the first half of the 19th century

a small number of families of Jewish dyers were expelled from Bukhara and chose to relocate in Khiva. Ye. Kileveyn recorded that in 1856 there

were approximately ten families of Jews living in Khiva engaged in dyeing and viniculture. They had re-established their craft of silk tying and

dyeing, producing just three adras patterns for the manufacture of chapans for the Khivan market. Some of this cloth, or the chapans

made from it, found its way into Karakalpakia. It was used for making a special pashshayı ko'ylek wedding dress and somehow became

the fabric of choice for sewing kiymesheks.

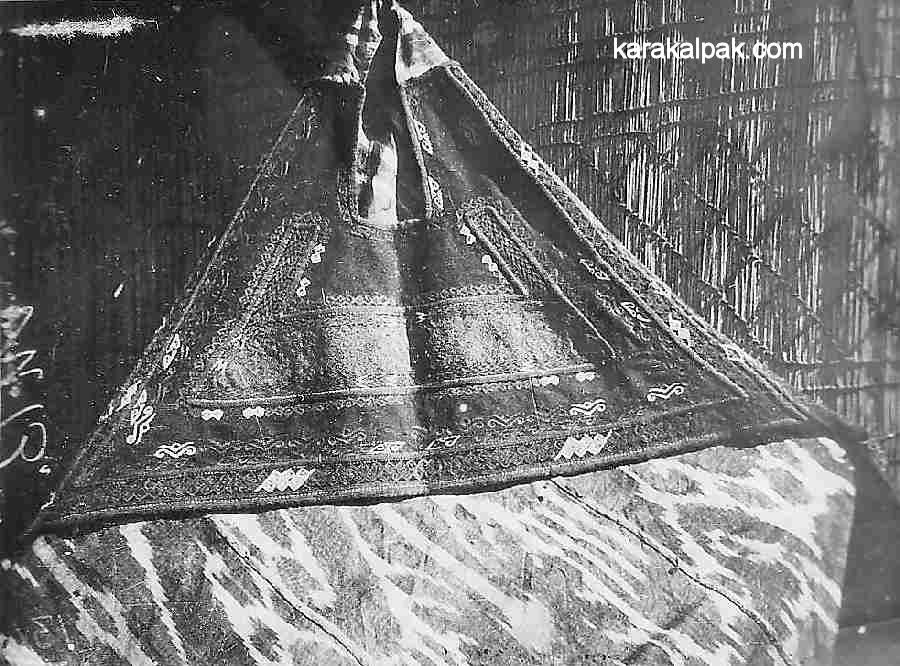

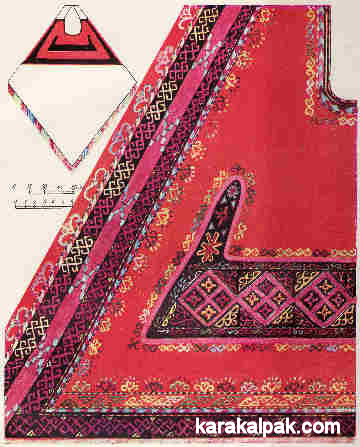

As we know from our work on dating, the Karakalpaks were already making cross-stitch qızıl kiymesheks during the last decade

of the 19th century, embroidering a strip of chequered shatırash and attaching it to an aldı of red ushıga . The

first description of such a kiymeshek was written by Anna Rossikova who travelled down the Amu Darya to visit the Amu Darya Otdel

in 1902. Rossikova first observed that the local Qazaq women wore only one form of headdress the dzhaulyk turban. She applied the

same term to the Karakalpak oramal:

"As far as the costume of the Karakalpak woman, especially where the headgear is concerned, it is unique and extremely original. Usually like Kirghiz [Qazaq] women, they wind around the head a "dzhaulyk" turban, but for going out and on all festive occasions they put on the caps, known by the name of "kimeshek-keste". Each Karakalpak woman has this unique head detail. It is sewn as follows. A right-angled triangle is cut out of some material, into which a circular opening is made, the size of the face of an adult person. The opening is trimmed with something, and all the vacant spaces around it are embroidered with multi-coloured silks; moreover the sewing is completed in such a way as our Ukrainians embroider with the smallest of crosses, but the patterns of this sewing have nothing in common with our Russian or Ukrainian ones. Whoever saw Asian carpets, they would find much in common with the Karakalpak embroidery patterns. According to their means, a large silk shawl of Bukharan production or a woollen one is sewn to two sides of the triangle, in such a way that the corner of the shawl aligns with the corner of the triangle: the free ends of the shawl fall on the back down to the hem [of the dress]. The result is something resembling a Caucasian hood. The "kimeshe-keste" is slipped over the head, covering the breast at the front; all that is revealed is the face for which the opening is made. I saw no other special features in the costume of Karakalpak women."It is absolutely clear that Rossikova is referring to a cross-stitch qızıl kiymeshek, from the nature of the stitch and the length and material of the silk tail. Clearly Rossikova had no idea that the "Bukharan silk" was actually made in Khiva.

|

|

|

|

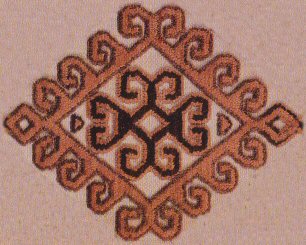

The pattern on the uppermost kiymeshek image is unclear, although the Khorezmian adras is obvious. The second kiymeshek

has the shayan quyrıq pattern, while the fourth has the qoralı gu'l pattern.

On 16 May 1929 the new Regional Studies Museum opened in To'rtku'l with an exhibition of some of the costumes, artefacts, and photographs

collected by Melkov over the previous seven months.

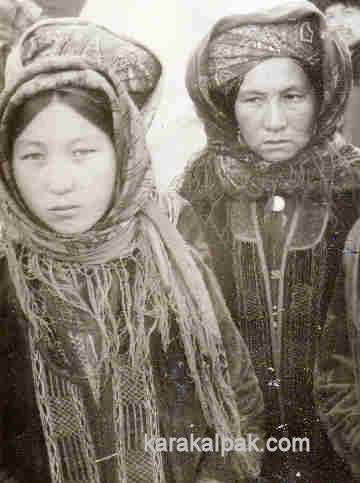

Even in the late 1920s the kiymeshek was becoming something of a rarity, at least in public. Morozova mentions that she once saw a young

woman in a kiymeshek when she was working in the Ko'k o'zek region near Qarao'zek in 1927. She was wearing a pashshayı ton,

an expensive fur coat with an outer facing of pashshayı silk adras, with a kiymeshek over the top. Around her head

she had a turban of red silk kerchiefs with a light floral wool kerchief with tassels tied above the turban. Morozova asked her why she was not

wearing a jegde as well. She replied haughtily: "Who wears a jegde with a kiymeshek? It is not the custom".

However Lobacheva's field research from 1956 to 1959 established that the qızıl kiymeshek was still being used as a wedding

garment as late as 1936, according to one of her informers from the Mu'yten-Teli clan in Moynaq region. Another Karakalpak woman said that she

was married in 1935 in a kiymeshek made by her mother in 1918. Finally a Mu'yten-Samat women said that it was used on Mergentaw Island

up to around 1926.

|

According to Zakharova and Khodzheava, the more nomadic Qazaqs held on to their kimesheks somewhat longer. By the 1930s they were starting

to go out of fashion in the northern and eastern regions of the Qazaq Republic, but were still preserved among the elderly.

There were several reasons why the kiymeshek gradually went out of fashion in the late 1920s. The first was socio-economic. Following the

formation of the Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast in 1925, young women were increasingly encouraged to leave the home and join the agricultural

workforce. There was less time available for home-based crafts such as embroidery. For the first time ever Karakalpak women had a limited degree of

financial independance. At the same time there was an increasing supply of affordable Russian-manufactured kerchiefs and other textiles for them to

buy. Another factor that may have occurred at around this time is that the production of adras probably came to a halt in Khiva. In Bukhara

many Jewish families had relocated to Ferghana in the last quarter of the 19th century and others escaped from Tsarist discrimination at the turn of the

century by emigrating to Palestine. Following the Soviet takeover a second wave of emigration occurred between 1924 and 1935, firstly to Afghanistan

and Iran and later to Palestine. It is possible that the small Khivan Jewish community also departed at some time during this period.

Married women continued to cover their hair with the oramal, tied in different styles according to region, over which they draped a large

Russian-manufactured kerchief. This could be replaced by a qızıl jegde for festival occasions:

|

During the 1930s the Karakalpaks experienced an even greater transformation in their lifestyles. On International Women's Day in 1927 the

Soviets launched the hujum, a campaign to eradicate the female veil, targeted in the Uzbek and Tajik population against the paranja

and chachvon. It had no impact whatsoever in distant Karakalpakia (or even Khorezm for that matter), where Karakalpak women never veiled

their faces anyway apart from during the wedding ceremony. However it was the start of a long process in which the State would take an

ever-increasing control of the way people lived and even thought.

|

Of far greater immediate significance was Stalin's first Five Year Plan, which was adopted at the 16th Party Conference in April 1929. It

ambitiously targeted a 150% increase in agricultural production, along with cotton self-sufficiency, to be achieved through the collectivization

and modernization of farms. The farmlands and property of the so-called kulaks, private landowners and farmers, would be expropriated and

held collectively, eliminating the hard core of anti-Soviet resistance in the settled agricultural areas. In Karakalpakia collectivization was

implemented in the early part of the 1930s. At the start of 1929 all farms were privately owned, but by the end of 1932, 88½% of livestock was

held by either kolxoz or sovxoz collective farms. Of course before these changes most Karakalpaks in the delta lived within

extended families that essentially operated as a collective unit anyway, and the collectivization process involved little more than combining several

family groups into a single economic unit. For the wealthiest Karakalpaks however the changes were catastrophic - their property, including their

festival costumes, was confiscated, although many attempted to conceal their possessions from officials.

|

As the area under cultivation was expanded, so more and more women were brought into the workforce. Women's rights became enshrined in law and

various initiatives were launched to involve women in the social, economic, and political life of their district. Anti-religious pressure intensified,

partly through a drive known as the "Movement of the Godless". Some attempted to resist these pressures and were persecuted by Bolshevik officials.

Over time the wearing of any type of traditional costume became seen as a sign of rebellion. People became fearful and some deliberately destroyed

their traditional costumes.

We have spoken to many old women over the last fifteen years who explained that in the 1930s they had less and less time to pursue traditional female

crafts. Some had no interest in embroidery or weaving in the first place and found that work gave them increased freedom and their own independent

income. By 1934 most women had ceased to embroider.

|

Established in 1937 but interrupted by the war, Sergey Tolstov's Khorezm Expedition began its programme of ethnographical research in 1945 under

the leadership of Tatyana Zhdanko with the support of Bella Vaynberg, Nina Lobacheva, Igor Savitsky, Xojamet Esbergenov and others. Zhdanko

records that they discovered an aq kiymeshek at the kolxoz named after Axunbabaev in Shımbay district in 1949 as if this was a unique find.

Described as a kempir or old woman's kiymeshek, it was illustrated but not published until 1958 see later below.

Qızıl kiymesheks were also located and beautifully illustrated:

|

|

When Tatyana Zhdanko wrote about life at the kolxoz named after Axunbabaev at that time, she concluded that the equal participation of women in

kolxoz work and the equal status granted to them by Soviet legislation had transformed family life. As regards the kiymeshek:

"The red cloth headgear, richly ornamented with embroidery, and also the local variety of yarmak have either gone out of fashion or are only surviving as a domestic relic".Zhdanko's reference to a yarmak is confusing. Is she referring to a face veil similar to the Turkish yashmak or to the Uzbek chachvon? As we have already noted, ordinary Karakalpak women did not veil the face.

|

|

Surprisingly Zhdanko never published a serious study of these garments, although Lobacheva wrote a short paper some forty years later.

Lobacheva found that the kiymeshek was still well-known in the late 1950s and that a qızıl kiymeshek could be found

as a family relic in almost every home. A little later Zhdanko found several Mu'yten families on the islands of the southern Aral Sea who still

kept qızıl kiymesheks as valuable family heirlooms.

|

The Khorezm Expedition collected examples of national costume including qızıl kiymesheks from 1956-1974, most of their finds

being spread across the northern region of Karakalpakstan. However most old women refused to sell their kiymesheks, explaining that without

that garment they would not only feel sinful but would be looked down upon by their family and neighbours. The kiymeshek had been an

indispensable garment for all married women, without which they could not even approach their father-in-law or their husband's elder brother.

Although a relic of the past, the kiymeshek remains a powerful symbol of traditional Karakalpak material culture and frequently reappears

in various forms:

|

In 2002 we visited a small exhibition staged by a secondary school in the city of No'kis and were delighted to see reproductions of aq and

qızıl kiymesheks:

|

|

Families with an heirloom kiymeshek can still be found today, although their number is rapidly dwindling. The older generation remain

nostalgic about their traditional culture and are keen to retain their heirlooms. However as they pass away their sons and daughters are more

interested in trading the family kiymeshek for some ready cash to alleviate the family budget. Over the past decade kiymesheks

have been turning up in Istanbul, in the tourist bazaars of Bukhara, and even on the internet.

|

In the mid-1960s Shalekenov observed that among the Qazaq women of the lower Amu Darya the kimeshek was still being worn by the elderly.

Surprisingly one can still occasionally see an old Qazaq woman wearing the aq kimeshek on the streets of Karakalpakstan today, at the start

of the twenty-first century. However their days are numbered and they will soon be gone. The fascinating tradition of the kimeshek head veil

will die alongside them.

Where to see Karakalpak Kiymesheks

There is only one place to see a good range of Karakalpak kiymesheks and that is in No'kis, the capital of Karakalpakstan. A selection of

kiymesheks, both aq and qızıl, was displayed at both major museums.

The State Museum of Art named after Igor Savitsky has the largest collection of kiymesheks in the world -

171 complete qızıl kiymesheks, 165 qızıl kiymeshek aldıs, 105 qızıl

kiymeshek quyrıqs, 1 complete aq kiymeshek, and 35 aq kiymeshek aldıs. Although only a minority are on public

display behind glass in the first floor costume gallery, these tend to be their best. For detailed information on visiting this museum see

our Sightseeing page.

The Regional Studies Museum had the second-largest collection 108 complete qızıl

kiymesheks, 56 qızıl kiymeshek aldıs, 1 complete aq kiymeshek, and 4 aq kiymeshek aldıs.

Two of them were spectacular, one being the only example with a quyrıq made from Khorezmian sarı pashshayiı.

They also had a complete Qazaq kimeshek. Unfortunately this museum closed in 2010 and the building was demolished. A new building housing

this museum may open in the city centre in 2012.

One additional qızıl kiymeshek is displayed at the small but interesting Shamuratov House Museum, just around the corner from

the Savitsky Museum.

In Russia the only kiymeshek on public display in the past has been at the Museum of Oriental Art in Moscow.

In Europe there is one qızıl kiymeshek in the Linden Museum in Stuttgart.

References

Alikhanov-Avarskiy, M., The March on Khiva (Caucasus Force) 1873, Steppe and Oasis [in Russian], The Russian Herald, Saint Petersburg, 1879,

reprinted on the 25th anniversary by Ya. I. Liberman, Saint Petersburg, 1899.

Andrianov, B. V., and Melkov, A. S., Forms of Karakalpak Peoples Ornament [in Russian], Works of the Khorezm Archaeological-Ethnographical

Expedition, Volume III, Materials and Research on Karakalpak Ethnography, pages 411 onwards, Academy of Sciences, Moscow 1958.

Bardanes, C., Tagebuch über seine Reisen in der Kirgisischen Steppe mit des Herrn Professor Falks [in German], addendum to

Beyträge zur topographischen Kenntniss des Russischen Reichs, Volume 1, by Johann Peter Falk, Kaiserl. Academie der

Wissenschaften, Saint Petersburg, 1785.

Canby, S. R., Safavid Painting, The Hunt for Paradise: Court Arts of Safavid Iran, 1501-1576, edited by J. Thompson and S. R. Canby, pages 73 to 133,

Skira Editore, Milan, 2003.

Dal', V., The Story of the Prisoner Fedor Fedorov Grushin [in Russian], http://kungrad.com/history/biblio/plen/

de Levchine, A., Description des Hordes et des Steppes des Kirghiz-Kazakhs, translated from the 1832 Saint Petersburg publication

by Ferry de Pigny, L'Imprimerie Royale, Paris, 1840.

Dzhanderkin, K., The Prospects for Socialist Stock Raising in the Karakalpak ASSR, Karakalpakia: Work of the First Conference on the Study

of the Productive Power of the Karakalpak ASSR [in Russian], Volume II, pages 113 to 130, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Leningrad, 1934.

Falk, J. P., Beyträge zur topographischen Kenntniss des Russischen Reichs [in German], Volume 2, Kaiserl. Academie der

Wissenschaften, Saint Petersburg, 1785.

Fitzgerald, E., translator, Rubâiyât of Omar Khayyâm and Persian Miniatures, Productions Liber, Friberg, 1979.

Fitz Gibbon, K., and Hale, A., Ikat Silks of Central Asia, Laurence King Publishers, London, 1997.

Galerkina, O., Mawarannahr Book Painting, Aurora Art Publishers, Leningrad, 1980.

Georgi, J. G., A Description of All the Nationalities that Inhabit the Russian State [in Russian], Volume 2, Saint Petersburg, 1776 to 1777.

Gladyshev, D. V., and Muravin, I., Journey from Orsk to Khiva and back, completed in 1740-1741 [in Russian], Geographical Proceedings, Issue 4,

published by the Russian Geographical Society, St Petersburg, 1850.

Karazin, N. N., In the lower reaches of the river Amu: Travel Descriptions [in Russian], Herald of Europe, Book 3, 1875.

Kaulbars, A. V., Lower reaches of the Amu Darya, described from his own research in 1873 [in Russian], Transactions of the Russian Geographical

Society, Volume 9, Saint Petersburg, 1881.

Kubičková, V., Persian Miniatures, translated by R. Finlayson-Samsour, Spring Books, London, 1961.

Lillys, W., Reiff, R., and Esin, E., Oriental Miniatures: Persian, Indian, Turkish, Souvenir Press, London, 1965.

Lobacheva, N. P., On the History of Central Asiatic Costume - the Karakalpak Kiymeshek [in Russian], from Report of the Field Studies, edited by

Z. P. Sokolov, pages 54 to 73, Miklukho-Maklaya Institute of Ethnography and Anthropology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 2000.

MacGahan, J. A., Campaigning on the Oxus and the Fall of Khiva, Harper & Brothers, New York, 1874.

Meyendorff, G. de, Voyage d'Orenbourg à Boukhara fait en 1820, Librairie Orientale de Dondey-Dupré Pere et Fils, Paris, 1826.

Morazova, A. S., The Domestic Cultural Life of the Karakalpaks [in Russian], Doctoral Thesis, Department of History, Academy of Sciences of the

Uzbek SSR, Tashkent, 1954.

Moser, H., A travers l'Asie Centrale, E. Plon, Nourrit et Cie., Paris, 1885.

Muravyev, N., Journey to Khiva through the Turkoman Country [in Russian], Oguz Press, London, 1977.

Northrop, D., Veiled Empire: Gender and Power in Stalinist Central Asia,

Pallas, P. S., Reise durch verschiedene Provinzen Russischen Reichs, Volume 1, Kanserlichen Academie der Wissenschaft,

Saint Petersburg, 1771.

Pallas, P. S., Kupfer zu P. S. Pallas Neuen Reisen in die südlichen Statthalterschaften des Russischen Reich in den Jahren 1793 und 1794,

Martini, Leipzig, 1799.

Rakhimova, Z. I., Central Asian Women's Costume in the Miniatures of Maveranna from the 16th to 17th Centuries, Culture of the Middle East

[in Russian], pages 135 to 157, FAN, Tashkent, 1990.

Rossikova, A. E., On the Amu Darya from Petro-Aleksandrov to Nukus [in Russian], Russian Bulletin, Number 8, pages 562 to 588, Saint Petersburg, 1902.

Sadykov, A. S., Economic relationship of Khiva with Russia in the second half of the 19th to the beginning of the 20th century [in Russian], Science,

Uzbek SSR, Tashkent, 1965.

Sazonova, M. V., Women's Costume of the Uzbeks of Khorezm [in Russian], Traditional Clothing of the Peoples of Central Asia and Kazakhstan, Academy of

Sciences of the USSR, Publisher Nauk, Moscow, 1989.

Schuyler, E., Turkestan, Notes on a Journey in Russian Turkestan, Khokand, Bukhara and Kuldja, Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, London, 1876.

Shalekenov, U. Kh., Kazakhs of the Lower Amu Darya [in Russian], Fan Publishing, Tashkent, 1966.

Sobolyev, L. N., Letters about the Amu-Darya expedition [in Russian], The Russian Invalid, Saint Petersburg, 1874

Spalding, H., translator, Khiva and Turkestan, Chapman and Hall, London, 1874.

Sukhareva, O. A., Ancient Features in the Types of Headwear of the Peoples of Central Asia [in Russian], Central Asian Ethnographic Collection,

edited by S. P. Tolstov and T. A. Zhdanko, pages 305 to 308, Academy of Science of the USSR, Moscow, 1954.

Titley, N. M., Persian Miniature Painting, The British Library, London, 1983.

Tolstova, L. S., Materials of the Ethnographical Inspection of the "Karakalpak" Group of the Samarkand Region of the Uzbek SSSR [in Russian],

Soviet Ethnography, Volume 3, pages 34 to 44, Academy of Science of the USSR, Moscow, May-June 1961.

Tolstova, L. S., The Kara-Kalpaks of Fergana, Central Asian Review, Volume 9, pages 45 to 52, 1961.

Vambery, A., Travels in Central Asia, Praeger Publishers, New York, 1970.

Vambery, A., Sketches of Central Asia, Wm. H. Allen & Co., London, 1868.

von Herbestein, S., Rerum Moscoviticarum Commentarii, translated by R. H. Major, The Hakluyt Society, London, 1851.

Wood, H., The Shores of Lake Aral, Smith, Elder, & Co., London, 1876.

Zakharova, I. V., and Khodzhayeva, R. D., The Head-gear of the Kazakhs [in Russian], Traditional Clothing of the Peoples of Central Asia and Kazakhstan,

edited by N. P. Lobacheva and M. V. Sazonova, pages 216 to 227, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, 1989.

Zerrnickel, M., The Karakalpak Kyzyl Kiymeshek a Head, Chest, Back Veil [in German], Tribus Year Book, Number 34, Linden Museum, Stuttgart, 1985.

Zhdanko, T. A., Everyday Life in a Karakalpak Kolkhoz Aul [in Russian], Soviet Ethnography, Number 2, 1949.

Zhdanko, T A, Karakalpaks of the Khorezm Oasis [in Russian], Works of the Archaeological and Ethnographical Expedition to Khorezm, 1945-48, Volume 1,

edited by S. P. Tolstov and T. A. Zhdanko, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, 1952.

Zhdanko, T. A., The Survival of Feudal-Patriarchal relationships in the Private Life of Karakalpaks [in Russian], pages 505 to 519, Works of the

Archaeological and Ethnographical Expedition to Khorezm, 1945-48, Volume 1, edited by S. P. Tolstov and T. A. Zhdanko, Academy of Sciences of the

USSR, Moscow, 1952.

Zhdanko, T. A., The Ornamental Folk Art of the Karakalpak People [in Russian], from Materials and Research on the Ethnography of the Karakalpak,

edited by T. A. Zhdanko, pages 373 to 410, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, 1958.

Zhdanko, T. A., Life of the Kolkhozniks of the Fishing Artels on the Islands of the Southern Aral [in Russian], Materials and Studies on the

Ethnography and Anthropology of the USSR, pages 27 to 43, Soviet Ethnography, Number 5, 1960.

Visit our sister site www.qaraqalpaq.com, which uses the correct transliteration, Qaraqalpaq, rather than the

Russian transliteration, Karakalpak.

|

This page was first published on 7 March 2008. It was last updated on 6 February 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2015. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |