|

The Karakalpaks are a heterogenous people, their appearance ranging from European to Mongoloid. They are a confederation

of many tribes, organized into two major divisions or arıs, the On To'rt Urıw (meaning fourteen tribes) and the Qon'ırat.

A recent French study of the DNA from men belonging to both arıs has shown that although there are strong genetic

relationships within individual Karakalpak clans, these relationships are not shared from clan to clan. This confirms the

historical evidence, which suggests that the Karakalpaks are a confederation of different tribes with no common origin,

just like the neighbouring Uzbeks, Qazaqs, and Turkmen.

The world population of Karakalpaks is probably less than 600,000, making them one of the smallest Turkic groups in Central Asia.

About 80% live in the Autonomous Republic of Karakalpakstan, the remainder being mainly located in other parts of Uzbekistan,

Kazakhstan, and Russia. For comparison, the Qazaqs may number up to 14 million worldwide, of which only 8½ million (about 60%)

live in Kazakhstan. Surprisingly the Karakalpaks are not the dominant population of Karakalpakstan – they make up less than

one third of the population and are just outnumbered by Uzbeks, some of whom have moved into southern Karakalpakstan from other

parts of Uzbekistan in recent years.

The Karakalpaks speak Karakalpak, a language that belongs to the Qipchaq or north-western category of the Turkic-Altaic family

of languages, along with Qazaq, Bashkir, and Noghay. Of course the Karakalpaks would describe themselves as Karakalpak in the

Latin alphabet, not Karakalpak. The latter is the Russian transliteration of their name and this has subsequently become the

name most commonly used in the West. The Uzbeks call them Qoraqalpog.

The Karakalpaks are very close to the Qazaqs in more than language. The two groups have very similar traditional material

cultures and social customs. The limited archaeological and historical evidence available suggests that the Karakalpaks might

have formed as a confederation of tribes in the late 15th century or during the 16th century in a region of the lower Amu Darya

in close proximity to the Qazaqs of the Lesser Horde (or Junior Ju'z). The Karakalpaks spent a considerable time under Qazaq

domination and some of their tribes were led by Qazaq princes.

However whereas the Qazaqs were traditionally nomadic sheep-breeders and travelled widely across the steppes, the Karakalpaks

were semi-settled and only partly nomadic, pursuing a mixed pastoral-agricultural-fishing economy and breeding cattle rather

than sheep. They lived close to the rivers and marshes and migrated seasonally from their wintering grounds, or qıslaw,

to their summering grounds, or jazlaw, which were usually not too far apart from each other. Karakalpaks belonging to

the Qon'ırat arıs were more focused on cattle-breeding and fishing, whereas the more southerly dwelling On To'rt Urıw were

more heavily engaged in agriculture.

Clan identity remains very important to the Karakalpaks up to the present day and children are taught to value and respect their

clan from an early age. The majority of clans practise exogamy, meaning that a woman may not marry within her own clan. This

makes marriage a tough proposition for many young brides. They must leave their own family and village to go and live with the family

of the groom. In some households the youngest daughter-in-law is treated almost as a full-time family servant.

Throughout much of their history the Karakalpaks have battled against poverty and have been treated as underdogs by more dominant

ethnic groups. Their lives, families, grazing pastures, and possessions were constantly under threat from attack by marauding tribes,

whether Kalmuks in the 17th and 18th century, or Qazaqs, Khorezmian Uzbeks, and Turkmen in the 18th, 19th, and early 20th century.

Though their security improved following the arrival of the Russians in 1873, they have always remained economically inferior to

the neighbouring Uzbeks. Although they are now part of an independent Uzbekistan, they still face indifference, persecution, and

hostility from Uzbek politicians, government, and other officials. A Karakalpak visiting Tashkent keeps his ethnicity quiet if he

wants an easy life. If one requires a permit or some other official document, it is often preferable to claim to be Uzbek to avoid

the inevitable discrimination and deliberate delay.

Karakalpakstan is one of the two poorest regions of Uzbekistan, and the Karakalpak population suffers higher levels of poverty,

unemployment, and sickness than their Uzbek neighbours. A good monthly wage is about $20, and the majority of individuals have

to survive on much less. As elsewhere in Uzbekistan, wages are often paid several months in arrears and there is often a general

shortage of local currency – the Uzbek som.

Karakalpakstan has an isolated, closed, undeveloped, and inefficient economy primarily dependant on agriculture – mainly cotton and

rice growing. Less than 9% of the workforce is involved in industrial production. The region depends totally on support from

Tashkent – even at the most basic level there are not even any local sources of capital for investment. The discovery of large

gas reserves below the Ustyurt and Aral Sea will unfortunately do little for the local population. The exploitation of these

reserves will depend on money and expertise brought into the region from elsewhere, especially from Russia, and any economic

surplus will accumulate in government coffers in Tashkent. Natural gas extraction is a capital-intensive industry requiring only

a small specialist labour force for its management and maintainance.

The situation is made worse by the growing Aral Sea environmental disaster, which continues to adversely affect the northern

population of the Amu Darya delta – mainly the Qon'ırat Karakalpaks. The Aral fishing industry has been destroyed, much of the

surrounding agricultural land is turning into desert and even further south, secondary salinization – that ancient curse of the

Khorezmian farmer – has restricted the land available for cultivation. Local climate change, especially the reduction in rainfall,

is also affecting farmers further south. At the same time toxic residues remaining from past over-intensive use of pesticides

and defoliants on the cotton crop have polluted the ground water. Exacerbated by grossly inadequate levels of health care, this

has led to a high incidence of ailments and diseases, ranging from anaemia and tuberculosis to thyroid complaints and cancers.

One of the positive legacies from the Soviet period is that the overwhelming majority of children still go to school and adult

literacy is extremely high. However following Uzbek independence it is no longer obligatory to teach Russian and many good

schools now attempt to teach English as an alternate foreign language. In the past many older rural Karakalpaks never learnt

to speak Russian anyway, but now it is common to find young people in the cities who can only speak Karakalpak.

Today Karakalpaks can be divided into two types. The urban dwellers who live in Soviet-style apartment blocks, mostly located

in Biruniy, Taqıyatas, No'kis and Xojeli although some were also constructed for agricultural workers on kolxoz and

sovxoz collective or State farms, and the majority of the rural population who live in small single-storey adobe houses

or tams. The latter are also widespread in low-rise towns like Shımbay and Shomanay as well as in the suburbs of No'kis

and other big conurbations. Most Karakalpaks living in a tam maintain a small vegetable garden with some fruit trees

and a few chickens. Some might even have a cow and some goats. Indeed it is not unusual to see a herd of goats being taken through

the backstreets of No'kis to graze on some derelict site.

Such meagre resources can make an important difference to the family dinner table. Most Karakalpaks live on a high carbohydrate-diet,

based on bread, rice, pasta, potatoes, and other root vegetables. Commodities like meat, sausage, and cheese are relatively expensive

and only small amounts of meat and fish are served with an average meal. Tea is the universal beverage.

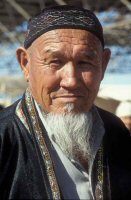

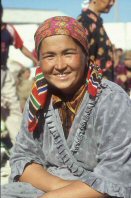

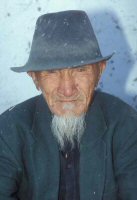

This view of Qon'ırat Sunday bazaar shows various examples of modern Karakalpak dress.

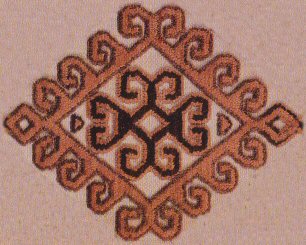

In the past the Karakalpaks had a distinct and colourful material culture – undoubtedly Turkic in origin yet uniquely Karakalpak.

This underwent a major revival in the early Soviet period as the income of Karakalpaks increased on the back of agricultural development

and increased cotton prices. But cotton is a demanding crop. Young women were needed to leave their homes to undertake backbreaking

work in the fields. They soon had little energy or time for weaving or embroidery. The wearing of traditional costume died out in the

1930s, while the production of yurts and yurt decorations declined substantially after the Great Patriotic War.

Today virtually all Karakalpaks wear modern Western clothes. Only a few remnants of traditional culture remain. In rural areas it

is still possible to see older men wearing a shapan purchased from the bazaar, or a skullcap. Many girls and women still

wear a headscarf, which is a relic of the former bas oramal or ma'deli headdress. Today young women aspire to be

married in the ubiquitous Western white wedding gown, the ultimate status symbol, although this is still not affordable for many.

The majority of Karakalpaks are Sunni Muslim, although only a tiny minority regularly attend a mosque, the latter being few and far

between throughout the delta. Beliefs are deeply held and traditions regarding birth, circumcision, marriage, and death firmly

adhered to. Karakalpaks maintain a mature, private, quiet, and tolerant attitude to their Islamic faith. Parents and the old are

respected and ancestors are venerated, their photographs hung in pride of place in most homes. Many Karakalpaks also maintain more

primitive beliefs and suspicions, such as the need to use various forms of amuletic protection against the evil eye.

Karakalpaks are overwhelmingly generous and hospitable (with one or two exceptions amongst the elite). Arrive unannounced at any

Karakalpak dwelling and you will be welcomed in as a stranger and offered tea and snacks, while the whole family will be brought in

from work to sit and chat. Stay long enough and the head of the family will offer to kill a chicken or sheep for a special welcoming

dinner – an expensive gesture for the host and a generous compliment to his honoured guests.

Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms

To listen to a Karakalpak pronounce any of the following words just click on the one you wish to hear. Please note that the dotless letter

'i' (ı) is pronounced 'uh'.

For a translation of this webpage into Romanian click here.

Visit our sister site www.qaraqalpaq.com, which uses the correct transliteration, Qaraqalpaq, rather than the

Russian transliteration, Karakalpak.

Return to top of page

Home Page

|

|

![]()

![]()