The Karakalpak Kiymeshek - Part 2

|

The Karakalpak Kiymeshek - Part 2

|

|

ContentsPart 1SummaryThe Karakalpak Kiymeshek Role of the Kiymeshek The Aq Kiymeshek The Qızıl Kiymeshek Part 2Different Qızıl Kiymeshek PatternsDistribution of Qızıl Kiymeshek Patterns The Dating of Qızıl Kiymesheks Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms References Part 3Other Kimeshek-Like GarmentsThe Qazaq Kimeshek The Uzbek Lyachek The Tajik Lachek and Kuluta The Turkmen Esgi, Lechek and Chember The Kyrgyz Elechek and Ileki The Khimar and Similar Islamic Veils References Part 4Previous Ideas on Kimeshek OriginsA Short History of Veiling up to the 16th Century References Part 5The History of the KimeshekWhere to see Karakalpak Kiymesheks References Different Qızıl Kiymeshek PatternsAs already mentioned qızıl kiymesheks can be classified into a variety of types according to the type of embroidery stitch used and the embroidery pattern (nag'ıs) applied to the orta qara:Cross-Stitch Qızıl Kiymesheks

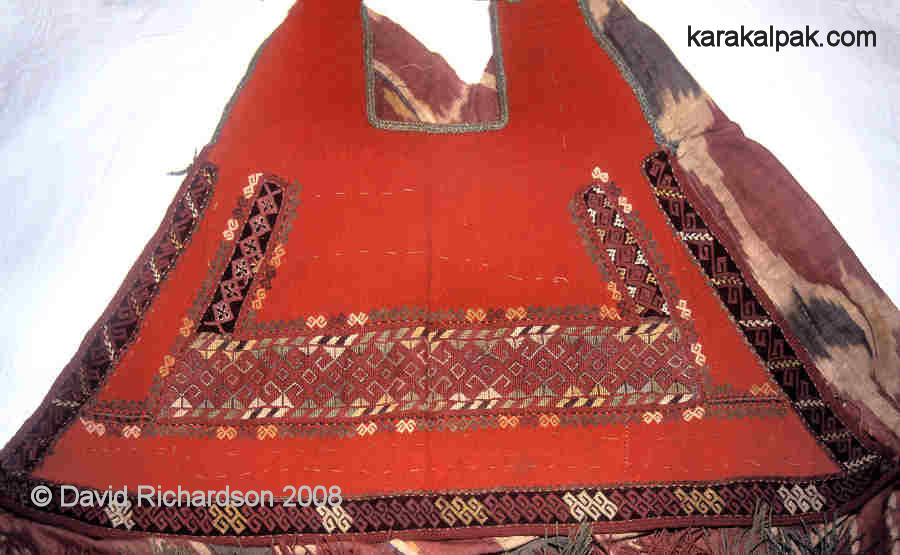

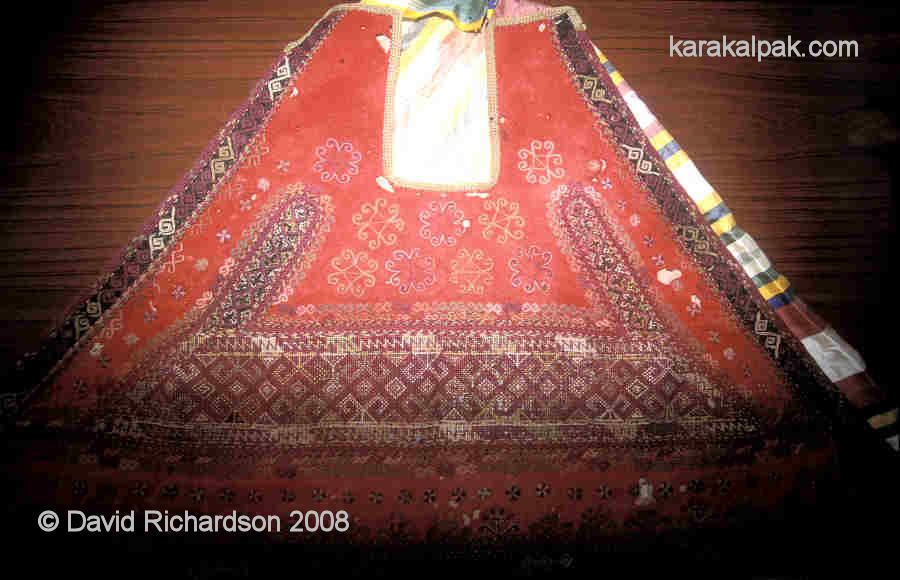

The cross-stitch pattern.

A cross-stitch qızıl kiymeshek, probably made between 1885 and 1890.

|

|

|

|

Some cross-stitch qızıl kiymesheks are clearly not original, since the qızıl ushıga

is much more recent than the original cross-stitch orta qara. Rather than waste a perfectly good strip of embroidery from a

damaged kiymeshek, the maker has recycled it to make a new garment.

|

In some cross-stitch qızıl kiymesheks the upward sloping ends of the orta qara were also embroidered in cross-stitch,

although in others they are embroidered in chain-stitch on a qara ushıga background. In most examples the outer edges

of the aldı have a narrow border of qara ushıga (the shettegi qara or edge black) embroidered in chain-stitch

and edged with red jiyek. Generally the only decoration on the qızıl ushıga consists of rows of

qos mu'yiz surrounding the orta qara and the shettegi qara. In a few examples however the areas below the face

opening and the orta qara were filled with cross-like and other individual motifs.

However the majority of qızıl kiymesheks were embroidered in chain-stitch and they can be classified into the following

six types:

|

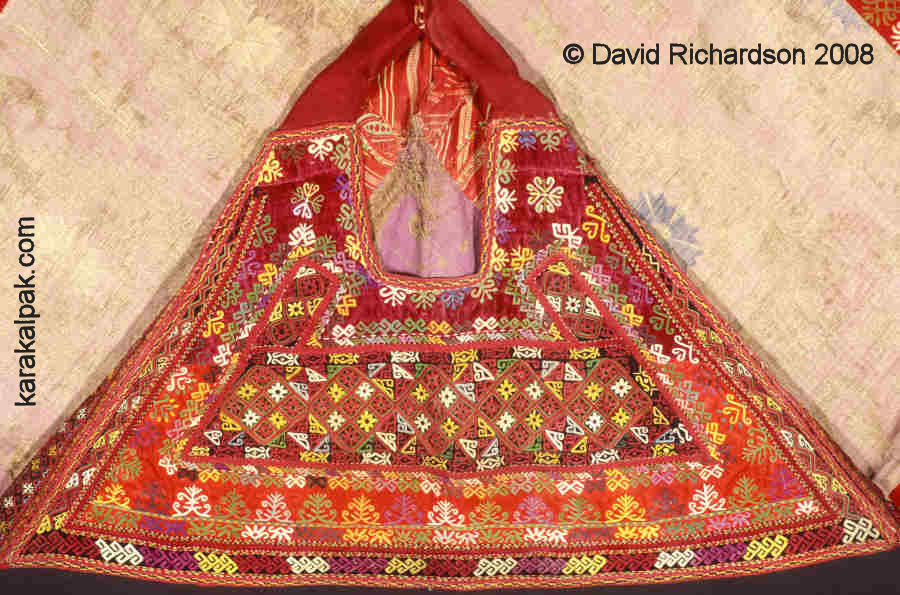

The qoralı gu'l, or fenced flower pattern, has a row of from five to nine diamonds each split diagonally into quadrants, each

quadrant containing an eight-petalled flower head. Allamuratov referred to this flower head as either an apricot flower, erik gu'l,

or a cotton flower, g'awasha gu'l, neither of which have eight petals!

|

The most common number of diamonds is seven. Sometimes the pattern has been poorly planned and includes an

incomplete diamond. The triangular spaces in between the diamonds can be filled either with floral motifs or with shiylawısh

(wood-plane) motifs.

|

|

There are at least four rare variants of this pattern:

|

|

In the last example, the upper half of the aldı is made from red machine-woven cord, while the bottom half is made from

qızıl ushıga.

|

The shayan quyrıq nag'ıs or scorpion's tail pattern is somewhat similar to the qoralı gu'l pattern,

except the diamonds are smaller and therefore greater in number. Furthermore the diamonds are not delineated, but the triangular spaces in between

them are, placing the visual emphasis on the latter. The pattern consequently appears as two rows of triangles, the apexes of the lower row touching

the apexes of the inverted upper row. The diamond-shaped spaces left in between contain various crosses, the arms of which usually contain one pair

of scorpion's tails and another pair of plant-like motifs.

|

|

|

Some of the cross-shaped motifs in the shayan quyrıq pattern sometimes resemble certain Qazaq motifs:

|

The Russian Ethnography Museum has a high proportion of shayan quyrıq patterns among its relatively small collection of

kiymesheks. Some were collected by Savitsky in the 1950s, but the example shown above was transferred from Moscow to Saint Petersburg

in the early 1940s and was most likely collected in Karakalpakia in the 1930s.

There is a second pattern type of this kiymeshek in which the crosses appear to be composed entirely of plant shaped motifs.

|

|

The number of pairs of triangles in the shayan quyrıq qızıl kiymeshek generally varies from nine to twelve, although

there are often additional lower triangles at each extreme end. However one example from the Tashkent History Museum - shown above - contains only

seven pairs of triangles. Each triangle is generally filled with yet smaller triangles and tiny floral motifs.

The scorpion's tail motif looks very similar to a reed head to us, and in the past we have referred to this pattern as qamıs

nag'ıs or reed pattern.

|

The segiz mu'yiz or eight horns pattern also has a row of diamonds, six or more in number, each containing an x-shaped cross and each

sprouting eight hooks or horns (the segiz mu'yiz motif). This pattern also appears in two different forms.

In the first form the segiz mu'yiz motif itself is not embroidered but appears as the qara ushıga background, outlined

in yellow and/or green chain-stitch, with an outer edging of red embroidery. Its red diamond-shaped centre contains a diagonally oriented cross

and generally four small circles. The segiz mu'yiz motif is quite distinct and has the appearance of an appliquéd figure.

|

|

In the second form the segiz mu'yiz motifs are less obvious, being embroidered in red chain-stitch and tending to merge with each other.

In some examples two of the motifs are embroidered in green. The centre of each motif contains a small diamond, inside of which a small cross

is usually embroidered . This version appears very similar to the mu'yiz pattern orta qara shown below.

|

|

In 75% of both types of segiz mu'yiz qızıl kiymesheks the outer border of the orta qara is decorated with the

ır'gaq or zigzag motif.

|

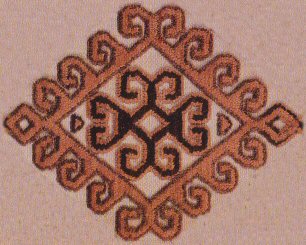

The mu'yiz nag'ıs or horns pattern consists of a complex lattice or matrix composed of small curled hooks or horns. This pattern

also comes in two forms. In the first form a dramatic red lattice covers the entire surface of the orta qara. The Karakalpaks sometimes

refer to this version as the shubal nag'ıs, meaning that the pattern has no beginning and no end.

|

|

|

In the second form the red lattice is not so wide, being enveloped by an outer border of ırg'aq or zigzag motif.

|

|

The latter version often contains small elements of green, sometimes expressed in the form of a diamond. Karakalpaks call this detailing

bawırsaq, after the small lozenge shaped pastry served at weddings and festivals.

|

|

This pattern shows that some Karakalpak embroiderers were completely innovative with their designs.

Distribution of Qızıl Kiymeshek Patterns

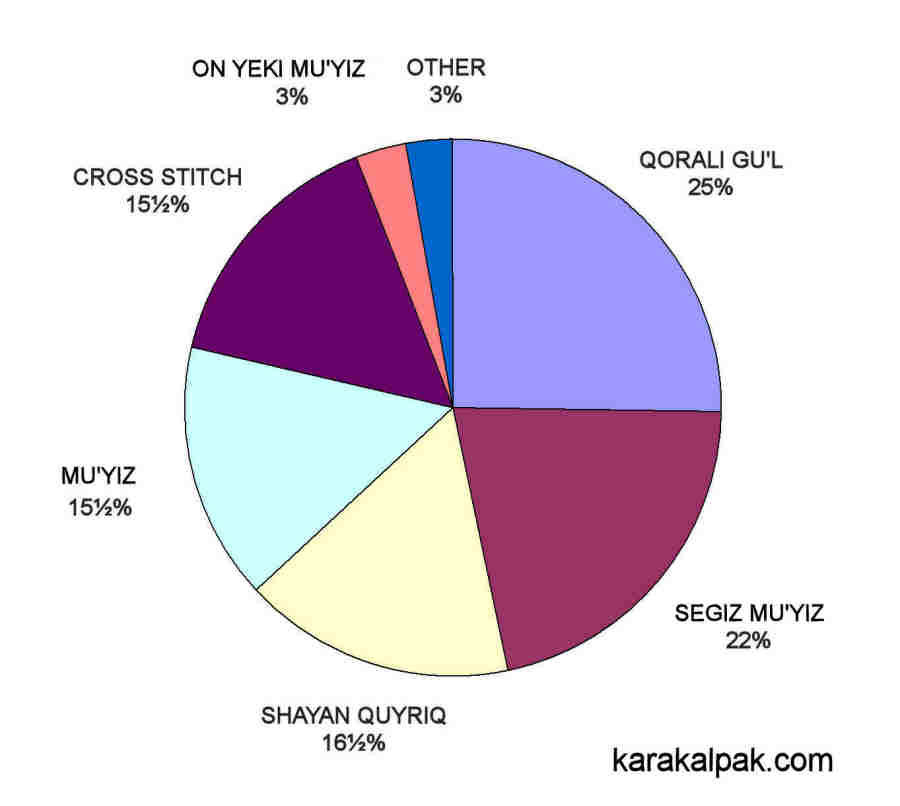

In order to shed light on the popularity of the various pattern types we have accumulated a sample of all the

qızıl kiymesheks that we have so far encountered in the field, in museums, and in private collections.

The sample covers a total of 103 kiymesheks.

The distribution of patterns within the sample is as follows:

|

The simple cross-stitch pattern accounts for just over 15% of kiymesheks in the sample, with the remaining 85% being chain-stitch.

However this may overstate the frequency of the cross-stitch pattern, since there is a relatively high incidence of this pattern in our own

collection. The Savitsky Museum have informed us that out of their inventory of 171 complete qızıl kiymesheks only

6 are of the cross-stitch pattern type – a frequency of less than 4%.

A better indicator would come from a full analysis of the complete inventories of both the Savitsky and the Regional Studies Museums in No'kis.

We have requested both museums to undertake this work and the Savitsky Museum have promised to do this when they can. With the latter museum

holding a total of 336 qızıl kiymesheks, 171 complete and 165 in the form of aldıs, this would provide a

much more representative result.

The majority of the chain-stitch patterns fall into four main types with not a great difference in their frequency of occurrence. Clearly the

qoralı gu'l pattern is the most common, followed by segiz mu'yiz and shayan quyrıq, all of which have

the same basic underlying design – a horizontal row of diamonds with interlocking triangles above and below. Of the main pattern types the

mu'yiz pattern has the lowest incidence in the sample. It is interesting that although many examples of this pattern have a uniform

lattice of horns, others show hints of the horizontal row of diamonds as an underlying design.

Note that within the segiz mu'yiz group roughly two thirds fall into the type 1 category and one third into the type 2 category.

Possibly the small on eki mu'yiz group, which accounts for only 3% of the sample, could be regarded as a sub-group of the segiz

mu'yiz category.

The existence of only four main pattern types of chain-stitch qızıl kiymeshek is a remarkable finding. Because the basic

elements of these patterns are so firmly established and were so strictly adhered to by embroiderers we suspect that they were originally

geographically- or tribe-specific.

Nina Lobacheva mentions that her original field notes referred to the different nag'ıs or patterns. She recalls that in the case of

the Mu'yten, "the design of the embroidery was allegedly always one and the same and the middle strip of the aldı was wider

than in other groups of Karakalpaks". She also refers to a Qoldawlı decoration, unfortunately without describing it. From these observations

she suggested that it was possible to assume that in the past several designs were associated with specific groups of Karakalpaks. However she added

that in the 1950s such associations were no longer remembered.

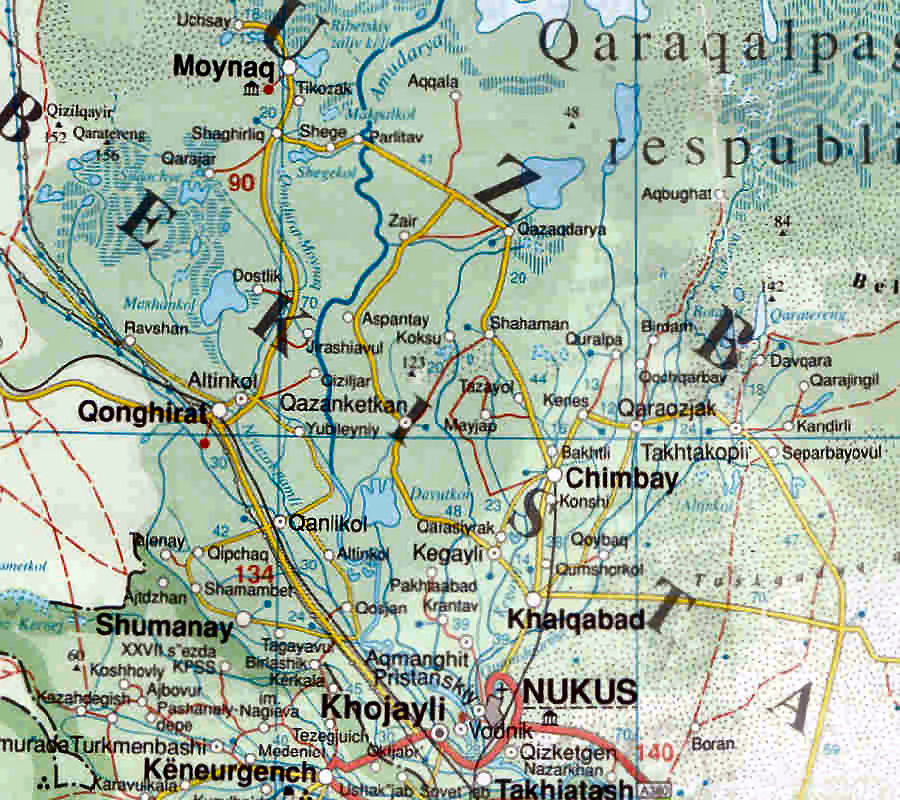

We have attempted to see if there is any correlation between the major pattern types and their geographical or tribal origin. This is difficult to

do, since the majority of museum kiymesheks have no provenance - their inventory cards show little more than the name of the donor and the

date of acquisition. Fortunately a small group of kiymesheks, including a number within our own collection, have better levels of provenance.

|

Cross-stitch qızıl kiymesheks seem to originate from different tribal groups from all parts of the delta. Two in the

Savitsky collection come from Moynaq, while the two in the Russian Ethnography Museum in Saint Petersburg come from Kegeyli region. In our

own collection, one comes from Xalqabad, one from Qarao'zek/Taxta Ko'pir, and three from Shımbay (Chimbay).

Let us look at the distribution of the four main chain-stitch patterns. Regarding the qoralı gu'l pattern we know that three

examples come from Qarao'zek, two come from No'kis (probably from families who have relocated south), one comes from Xalqabad, and another from

Kegeyli.

Of the eight segiz mu'yiz patterns where we have a geographical origin, three come from Qarao'zek, two come from Shege, one comes from

Taxta Ko'pir, one from Qanlikol, and one from Shımbay. There is clearly an association with the northern delta.

We have two shayan quyrıq pattern kiymesheks with very good provenance, the first made by a Mu'yten-Samat woman from

Qazaqdarya region, the other made by a Qoldawlı woman from Qon'ırat. Other examples come from Qarao'zek and Shomanay regions.

Karakalpak people have told us that they associate this pattern with the northern part of the delta.

Finally we have one mu'yiz nag'ıs kiymeshek with good provenance which was made by a Mu'yten-Samat on Terbenbes Island on the

southern shore of the Aral Sea. Several other examples come from No'kis, presumably from families who had relocated from rural locations.

The results are extremely incomplete and therefore far from conclusive. Furthermore they are complicated by the possibility that museum inventory

cards fail to record the movement of families from their original villages. Many of the Karakalpaks living along the southern coast of the Aral

Sea were relocated further south to regions like Qarao'zek during the 1950s, while a proportion of the general rural population has relocated to

No'kis since the Great Patriotic War. Even with these limitations it is still difficult to associate any one pattern with any particular location

or tribe. Nevertheless for all four patterns there is a strong link with the northernmost region of the Aral delta. This may indicate that the

different pattern types originated from different clan-tribal groupings rather than different regions. If there is a link, the Mu'yten and the

Qoldawlı seem to be most likely associated with the shayan quyrıq and mu'yiz patterns.

If there once was a tribal or regional bias to the different patterns, it is not surprising that it has subsequently disappeared. Although the

majority of Karakalpak clans are exogamous, during the 19th century people tended to marry partners from neighbouring villages in the same locality.

The increasing mobility associated with the 20th century meant that marriages were more likely between individuals from distant parts. As it was

always the girl who relocated to the village of her new husband, specific embroidery patterns must have been progressively introduced into other

regions. It is not surprising that nowadays every single pattern type can be encountered throughout the delta.

Dating of Qızıl Kiymesheks

Based on appearance the qızıl ushıga on many cross-stitch qızıl kiymesheks appears to be

much older than that on chain-stitch qızıl kiymesheks. Fortunately there are a number of kiymesheks where we

have sufficient provenance to estimate an approximate date of manufacture, so that we can test this observation.

Two museum examples suggest that cross-stitch qızıl kiymesheks date from the last decades of the 19th century:

|

This page was first published on 7 March 2008. It was last updated on 6 February 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2015. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |