The Karakalpak Postın

|

The Karakalpak Postın

|

|

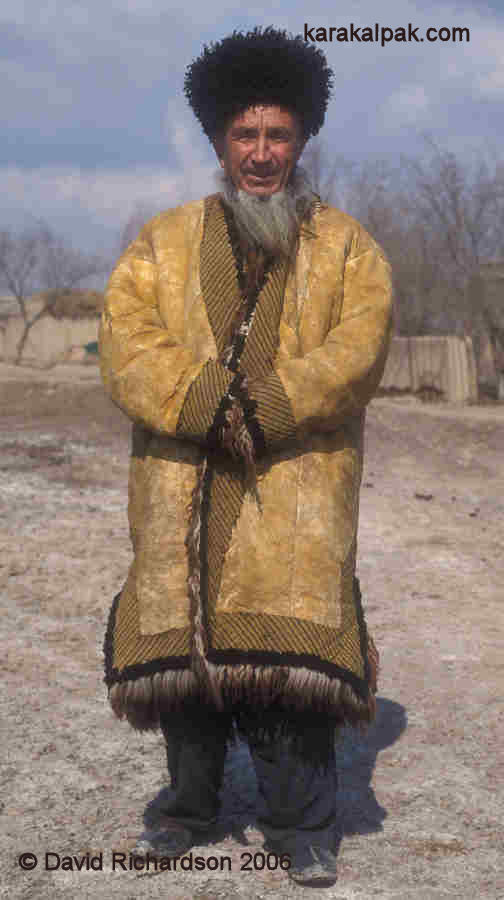

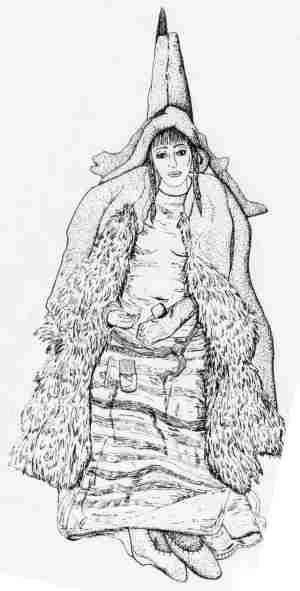

ContentsThe Karakalpak PostınAmuletic Properties Usage Terminology Distribution Manufacture Museum Collections History The Tayshaxı The Qılqa Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms References The Karakalpak PostınThe Karakalpak man’s postın is a heavy and bulky sheepskin overcoat, worn with the skin facing outwards and the fleece facing inwards. The outer sheepskin facing of the coat is dyed a light yellow colour and the outer edges – consisting of the collar and front panels and the coat bottom and the cuffs - are decorated with narrow strips of black or brown astrakhan pelt. These strips are bordered on the outside face of the coat with a band of striped, usually red, cloth which is often made of silk. A large triangular amulet, made from the same striped cloth and known as a jawırınsha decorates the back of the coat, just below the collar. The long woollen fleece is often exposed along the front and bottom edges of the coat and around the collar and cuffs. Obviously the inner fleece means that the coat requires no lining.

Two old Karakalpaks wearing postıns. Photographed by members of the the Khorezm Expedition in

the early 1970s.

|

|

The Karakalpak postın has always been an expensive piece of clothing and in the past only wealthy people or village leaders could afford one. Indeed there is a traditional saying:

"A holiday is only a holiday for a man who has a horse,Their value is indicated by the fact that less well-off men were sometimes handed down a second-hand postın from a wealthy friend or relative.

A festival is only a festival for a man who has a postın."

|

Interviews conducted with elderly local Karakalpak people by ethnographers from the Khorezm Archaeological and Ethnographical Expedition in the early

1970s established that the amulet acted as a talisman to protect the wearer against the "evil eye" -

the ancient and widespread folk belief that people can be harmed from the envious and malevolent stares of unfriendly people. The origins of such

beliefs lie in the depths of antiquity and clearly pre-date the conversion of the Qipchaq nomads to Islam during the era of the Golden Horde.

In this respect the postın is a unique item of male Karakalpak clothing - amulets were, and still are, widely used to protect

women of childbearing age, babies and children (especially boys), livestock and the yurt. However they are hardly ever worn by men, with the

one exception of the postın coat.

Usage

Its use among the Karakalpaks has been more associated with those living in the northern part of the delta – the Qon’ırat Karakalpaks -

rather than the On To'rt Urıw Karakalpaks living in the southern agricultural regions surrounding Urgench. The reasons for this difference

in usage are only partly ethnic and probably also reflect the fact that the northern delta has traditionally been a livestock-breeding rather

than an agricultural region and has always been neighboured by local communities of sheep-rearing Turkmen and Qazaq nomads. It also suffers

from a harsher winter climate.

Today the postın overcoat is rarely seen except in a few rural areas of the delta, and even then its use seems to be confined to

the elderly. The collectivization of the 1930s brought about profound changes in Karakalpak lifestyle and prosperity, leading to the increasing

adoption of Russian Western-style clothing. The land and property of the wealthy bays was confiscated and many were exiled. The new

emerging elite were Communist administrators and farm managers, who were more likely to achieve advancement by promoting an image of the modern

Russian official. The Great Patriotic War was an important watershed, after which many Karakalpak working men began wearing military-style

overcoats. Tatyana Zhdanko made a specific study of the Karakalpaks living in the kolxoz named after Axunbabaev in the district of Shımbay

around 1948 and observed that:

"Among the men, the old ones – though far more seldom than they do in Uzbekistan – wear the Oriental smocks and the national round sheepskin caps. Generally the men use trousers and jackets of urban cut or short sleeveless waistcoats of dark cloth, and very often quilted jackets or military tunics."

|

In 1958 Zadykhina published a study of the Uzbeks living in the Qıpshaq region of Karakalpakstan and noted that among the men: "Military field

shirts and overcoats are frequently encountered."

Terminology

The Karakalpaks use two alternative words to describe a man's sheepskin coat - postın and ton - as do many other tribal

confederations throughout Central Asia. The Karakalpak word postın is usually transliterated as postyn, pustin, or

pustyn in the Russian literature. The Uzbeks of Khorezm use the closely related words postin or pustin for a sheepskin

coat. The Uzbeks of Bukhara and the Kyrgyz use the term postun. The Pashtun of Afghanistan use the words postin and pushtin.

However the alternative Karakalpak word ton applies to more than just sheepskin coats, being used as a more general term that can apply

to any fur-lined coat. Sometimes the word ton is qualified, as in sen'sen' ton meaning a coat made from the skins of six-month-old

lambs, eltiri ton meaning a coat made from the skins of two-three month-old lambs, or ishik ton meaning a coat lined with animal fur

rather than sheepskin. The name ton is also used by the Qazaqs for both sheepskin and fur-lined coats, as well as by the northern and

southern Kyrgyz, and the Bashkirs.

According to Klavdiya Antipina, the word ton is used by the major southern Kyrgyz clan, the Adygine, and by the northern Kyrgyz. The name

postun is generally used by the Kyrgyz living in the Ferghana Valley as well as those belonging to the southern Ichkilik grouping, the latter

also using the word ton.

The Yomut Turkmen however refer to such coats as an ichmek. They too have a special version of the coat that is worn for celebrations and

festivals, known as a sikme ichmek, made from the skins of six-month-old lambs. The Tekke, however, use the word postun, while

the Saryks call such coats a possun.

|

|

The Karakalpaks use the word ishik to refer to a silk or cotton coat with a fur lining, especially a woman's fur-lined coat, sometimes

called an ishik ton. However the Karakalpak-English dictionary confusingly lists an ishik as a sheepskin jacket. The Qazaqs

similarily use the word ishik for a cloth coat lined with fur, although the definition of fur can encompass the woollen fleece of a sheep.

Klavdiya Antipina recorded that the southern Kyrgyz wore fur-lined coats known as ichiks, which originated from the neighbouring Uzbeks.

Again the definition of fur could include sheep fleece.

|

The fact that such coats are found in many different ethnic groups across Central Asia is indicative of their ancient origin. However the

existence of three different basic words to describe them points towards different cultural influences. The words teri for skin and

ton for fur are of Qipchaq origin and occur in the Codex Cumanicus. It seems that the word postin is of Iranian origin, the Persian

word pūst meaning a skin (pūst-i barra, lambskin). Possibly ichik is of Turkic origin (Oghuz?).

Distribution

The postın overcoat is by no means unique to the Karakalpaks and is very similar to coats worn by the neighbouring Uzbeks,

northern Yomut Turkmen, and Qazaqs of the Khorezm oasis. It occurs almost everywhere across Central Asia, ranging from the southern Turkmen,

the eastern Qazaqs, the northern and southern Kyrgyz, and the Tajiks, an observation recorded by S. P. Rusyaykin in 1959. Beyond Central Asia

it is found in Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and western Tibet.

We are unaware of any Karakalpak craftsmen still making postın coats today. Most modern Karakalpak postın seem

to be of Turkmen origin, imported from the Kunya Urgench region of the delta on the Turkmenistan side of the border. New postın

coats can be regularly seen on sale today at the Tolkuchka Sunday Bazaar in Ashgabat. They tend to be dyed an artificially bright yellow and

have prominent embroidery decoration along with a pair of leather laces for fastening the coat across the breast, neither of which are traditional.

|

Shalekenov noted that, in the winter, elderly Qazaq men living in the lower Amu Darya wore the Karakalpak postın sheepskin coat

rather than the traditional Qazaq sheepskin coat known as a ton.

|

However this obsevation may not have been absolutely correct. When Ella Maillart travelled through Taxta Ko'pir in 1932 she photographed men on

the local bazaar wearing belted overcoats that look very much like the Qazaq ton:

|

Later as she crossed the frozen Qizil Qum from Taxta Ko'pir to Kazalinsk, she photographed three Qazaq men with their grazing camels, one of whom is

standing and clearly wearing a belted and bulky sheepskin coat.

The form and the cut of the postın was similar to the Qazaq ton, the main differences being that the postın

was looser in fit and more greatly decorated than the ton.

Postun or ton were an almost universal item of male winter clothing for the nomadic Kyrgyz, especially at the higher altitudes.

Coats were even made for boys as young as three-years-old. Antipina noted that Kyrgyz sheepskin coats were decorated in a similar way to those from

Mongolia and the Altai, using strips of black velvet or sateen. The southern Kyrgyz from the western regions, close to present-day Uzbekistan,

followed the Uzbek fashion, adding triangles of black cloth to the back, sleeves, and sides. The southern Kyrgyz also had coats made in two different

colours, orange and white, some village communities preferring orange, others white. During the mid-20th century a new type of postun

emerged among the Kyrgyz featuring prominent sheepskin lapels.

In Afghanistan, too, postins were worn by men of all classes during the winter season. According to Dr Henry Bellew, the manufacture of

postins was a major industry in many towns and cities during the 19th century, including Kandahar, Ghazni, and Kabul. Postins made

in Kabul were considered to be the best and many were exported to Peshawar and beyond. Many of those made in Khandahar were exported to Pakistan.

Demand was particularily strong in 1857, since the Afghan postin had recently been adopted as the regulation winter dress of the Punjab army.

Manufacture

Postıns were traditionally made by master craftsmen, known as tonshı by the Karakalpaks and as postindoza or

postinchi by the Khorezmian Uzbeks. The main workshops were located in the major cities or larger settlements, Khiva being the most

significant centre of production in the Khorezm region. Here sheepskin and astrakhan pelts were processed for use in the manufacture of coats and caps,

some pelts even being exported to Bukhara to be made into coats by Bukharan masters. Postıns were usually sewn to order.

According to Zadykhina and Sazonova, one coat made of astrakhan lamb required eight or nine pelts taken from two- to three-month-old lambs. After

thorough cleaning the skins were coloured a light yellow or yellowish grey colour using a natural dye made from pomegranate skins steeped in a solution

of salt. The dye was known as anarpost in Karakalpak, anar being the word for pomegranate.

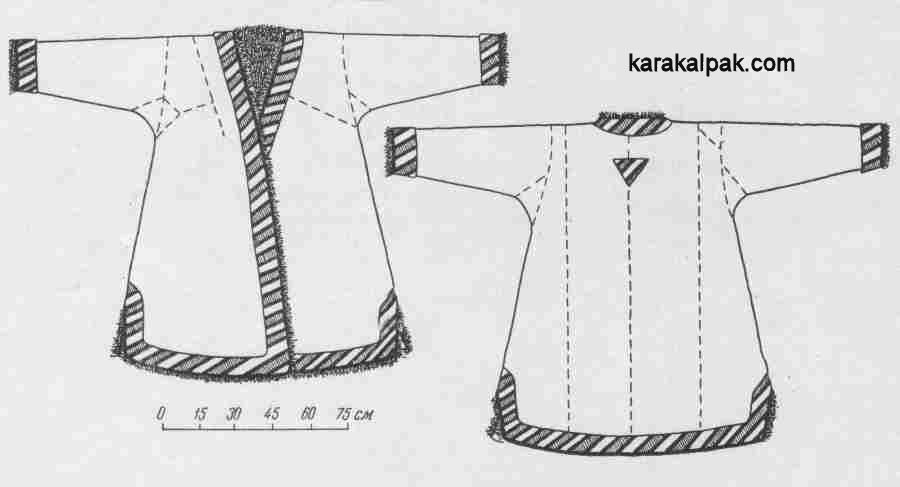

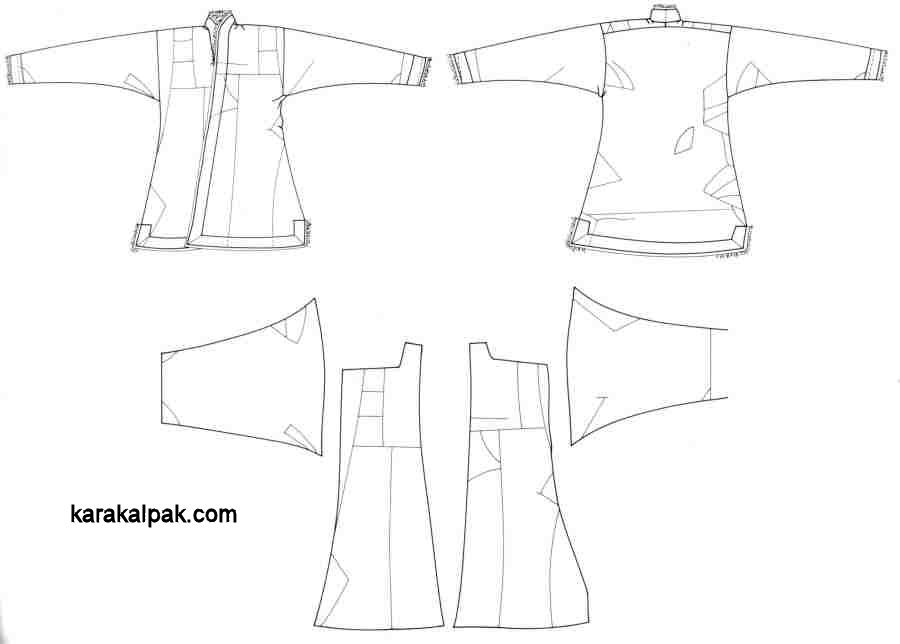

The cut of the sheepskin coat was similar to that of the khalat or shapan and was prescribed by long-established rules. No

significant deviation in the size of the postın was permitted - only the length of the coats could be varied. For making

measurements the postindoza used the span of a man’s hand from the little finger to the thumb, this length being known as a taxta.

For smaller measurements they used four finger widths.

|

The postın sheepskin coat was tailored in a similar manner to the quilted shapan. The treated pelts were sewn into

longitudinal strips, which were then joined side by side. A thin strip of yellow sheepskin leather was inserted into the seams joining the strips

for extra strength. The sleeves were made from transverse strips of sheepskin pelt, but in this case they did not place leather inserts within

the seams. The collar was normally made from darker hide, standing up at the rear and folding down into small lapels at the front. The bottom part

of the side seams were tailored with small slits for increased comfort. The edges of the collar, the cuffs, the front opening, and the bottom hem

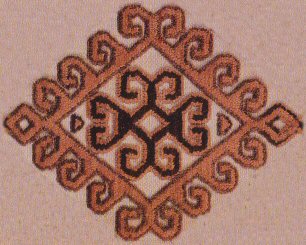

of the coat were usually finished with strips of black astrakhan or karakul, while the outer borders were decorated with bands of striped silk

cloth, cut on the bias so that the stripes were oriented diagonally. Karakalpak masters used red and black striped jipek, somewhat similar

to Khorezmian alasha, while Turkmen masters used various types of silk keteni. A triangle of the same material was sewn onto the

back of the coat to provide amuletic protection for the owner. Further decoration was sometimes added to the front panels at the bottom of the

collar, in the form of small embroidered red velvet triangles. The slits on the hem were also sometimes decorated with embroidery.

|

Nina Zadykhina and Mariya Sazonova report a comment recorded by V. Yu. Krupyanskaya from a master postindoza, whose father, grandfather,

and great-grandfather had also been postindozami. He said that 40 years earlier, in other words at some time between 1880 and 1890,

postindoza used embroidered cloth to make the triangular amulets rather than striped silk.

|

|

"G drove me to a street mainly inhabited by dealers in sheepskin. On entering one of the shops, we were nearly compelled to beat a retreat, owing to the smell. ... The sheepskins were in every stage of preparation. The heat thrown out by a heavy drying-stove was very great, and only the absolute necessity of ordering some warm clothes forced me to remain for an instant in the establishment."He went on to add that sheepskin garments were the warmest clothes that can be worn, despite their disagreeable smell.

Museum Collections

The only Karakalpak postın on public display in No'kis was at

the former Regional Studies Museum. Unfortunately this museum was closed and the building housing

it was demolished in 2010. It is hoped that it will reopen in a new city centre location in 2012.

|

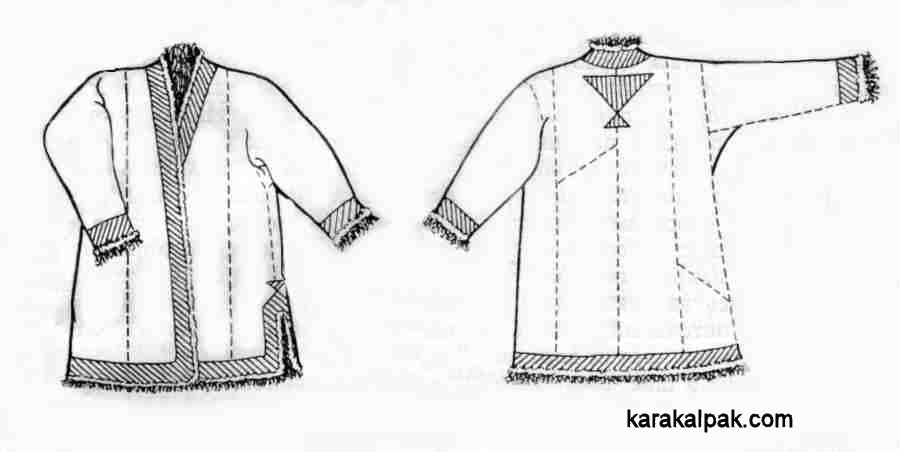

According to Esbergenov, one of the earliest examples of a Karakalpak postın was collected by S. P. Tolstov in 1934 for the Folk

Museum of the USSR. It was subsequently transferred to the State Museum of Ethnography of the USSR, Moscow. This example was brown in colour

and decorated with striped silk material. It had a straight cut and the sleeves were tapered from the shoulder to the cuff. It was 115cm long

and had a sleeve length of 66cm. It was made from several sheepskin pelts.

Some 40 years later, between 1971 and 1975, the Khorezm Archaeological and Ethnographical Expedition located several postıns and

photographed and measured them. One example was reported by Esbergenov as being dyed an ochre colour and was 117cm long, had a sleeve length

of 54cm and a side seam vent of 21cm. The width of the outer red striped silk decoration along the edges of the coat was 8cm, except on the cuffs

where it was 11½cm. The coat had a triangle with 29cm long sides sewn to the back. According to the maker the postın was sewn

from six to eight sheep's pelts.

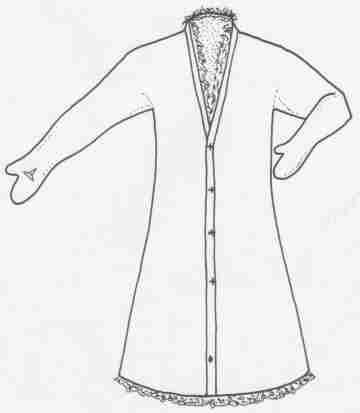

A rather well-worn Khivan Uzbek postin is held in the reserve collection of the Museum Department of the Ichan qala in Khiva:

|

In addition, there are two Bukharan Uzbek postins in the Ole Olufsen Collection at the Danish National Museum in Copenhagen.

History

The origin of the Karakalpak postın and the other similar coats found across Central Asia substantially predates the formation of the

Karakalpak, Uzbek, and Qazaq confederations. Sheepskin coats in general have been in use for several millennia across Central Asia. Indeed, given

the evidence that the domestication of sheep probably first took place in relatively nearby northern Iraq around about 9,000 BC, it is likely that

sheepskin pelts have been used to make coats and other items of costume in Western Asia since the early Neolithic and probably the Mesolithic era.

One of the earliest surviving fur-lined coats was found at the ancient burial site of Qizilchoqa (Red Hillock), discovered in 1978 close to the

Silk Road town of Hami, in the southern foothills of the Tien Shan in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region of western China. The cemetery has

been subsequently radiocarbon dated to about 800 to 530 BC. Among the many woollen textiles excavated from the site was a fur coat, made with

the fur turned inwards, and surprisingly incorporating an integral pair of gloves.

|

In the early 1990s the mummified body of a man, estimated to have been at least 55-years-old, was found next to the corpse of a woman in a shallow

grave at the nearby site of Subashi. This later site dates from about the 4th to the 3rd century BC. The man was wearing a heavy sheepskin coat,

worn with the fleece turned inside. Another grave contained the corpse of a woman wearing a calf-length sheepskin coat with sleeves, also made with

the fleece facing inwards. The coat was placed over her shoulders like a cloak. She also wore a tall black felt hat with a wide brim.

|

Although clothing specifically made from sheepskin was not identified in finds from the the more westerly kurgan burials at Pazyryk, in the Siberian

Altai, similarly dated to the 4th to 3rd century BC, other items of costume excavated from the site show that the tailoring of fur pelts and skins

had already reached a sophisticated level. Many items of clothing were fur-lined. Likewise the contemporary Scythian warriors depicted on the gold

and electrum vessels excavated from kurgan burials in the Ukraine are shown wearing finely tailored leather jerkins, beautifully decorated with braid

and fur edgings.

In 921 the government of the Abbasid Caliph Muqtadir sent an embassy from Baghdad to the king of the Bulgars on the Volga. The secretary to the

embassy, Ahmed ibn Fadlan, left us an extremely detailed account of the journey. The embassy sheltered from the harsh winter in Gurganj (now Kunya

Urgench), the capital of northern Khorezm. Ibn Fadlan survived by wrapping himself in clothing and furs, inside a Turkish yurt that had been

erected inside a house. It was so cold that the local people covered their water cisterns with coats lined with sheepskin fur. The coats were called

bustîns. In the second half of February 922 the embassy provisioned itself for the onward journey across the Ustyurt:

"The inhabitants of our host country kindly invited us to take our precautions with regard to clothing and advised us to carry a great quantity of it. During one frightening day they went over our venture and demonstrated the dangers to us. When we saw the reality through our own eyes we realised that it was twice as great as we had previously been told. Each one of us wore a tunic over a caftan, a fur-lined coat of sheepskin over a cardigan of felt and a bonnet which revealed only two eyes. Each one of us also had simple trousers and another thicker pair, slippers, boots of chagrin leather and over the boots some more boots, so that each one of us, when placed on top of the camel, could not move because of all this clothing."According to the Hudûd al-Âlam, compiled towards the end of the 10th century, the Kerder region of Khorezm (the Aral delta) was a major producer of sheepskins at that time.

"The sky was remarkably pure and brilliant. The air piercingly cold. I drew closer my posteen, or cloak of fur."Abbott recorded that postins were made from dhoomba's skins and made with the fur inside. The leather was tanned to the consistencey of wash leather (chamois), stained a buff colour and beautifully embroidered with floss silk. Their price was about 8 ducats or £4 each, a considerable sum of money at the time. This must have been a good quality coat, although Abbott commented that wealthy men wore coats of cloth lined with Siberian furs.

"Dreading, too, the cold we had been warned of, I enquired for a sheepskin shub, but could not find one to my taste in the bazaar, so poor was the choice."When Ole Olufsen was in Central Asia 1896-97 he collected two postins, both of which are held at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. The first, catalogued as inventory number 216, was acquired in the town of Osh in the Ferghana Valley (today part of Tajikistan) during 1897:

|

|

Olufsen described this as a Sart's sheepskin coat or chalat, made from the large wild Pamir sheep (Ovis poli). At that time the word

Sart was applied to all settled villagers throughout Turkestan, so the coat is likely to be Uzbek.

Olufsen's second coat, inventory number 9, was purchased in 1896 from the Kyrgyz of the Altai Steppe in the Northern Pamirs. It is decorated on the

outside with strips of plain blue velvet. Formally described as a chalat, Olufsen referred to it as a postun in his notes, adding

that the Pamir wild sheep was greatly valued for such coats in view of its long thick fleece. However because these were difficult to obtain at that

time, most people had to live with coats made from ordinary sheepskin.

Interestingly Olufsen must have been impressed by the qualities of the local postins, since he purchased a third for his own winter costume

for exploring the Pamirs.

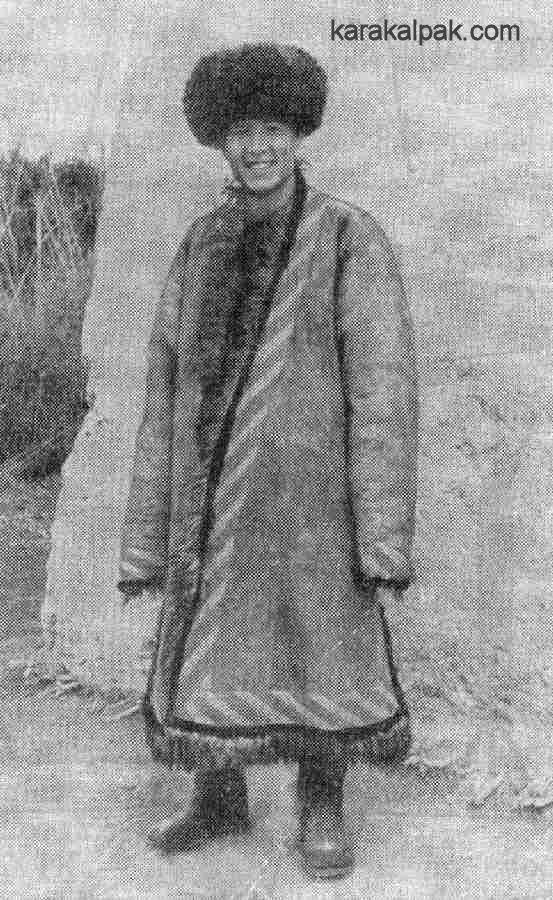

As elsewhere in Central Asia the Karakalpak postın remained in widespread use throughout the early part of the 20th century. However the

increasing availability of inexpensive military-style woollen overcoats from Russia gradually eroded the postıns popularity.

|

Even so it continued to be worn after the Great Patriotic War and can still be seen today in some of the remoter parts of the delta.

The Tayshaxı

In the past, Karakalpak men wore two different types of pelt coat – the tayshaxı and the qılqa. We have never seen

an example of either.

The tayshaxı was apparently a simple, undecorated knee-length coat made from a tayınshaq, the tanned pelt of a foal. It was

worn hair side out and was the traditional winter dress of shepherds and livestock farmers.

It is mentioned in an old Karakalpak saying:

"Hunger will force a man to clean husk from millet,It implies that the tayshaxı was the dress of the poor people who could only afford to live on millet.

Frost will force a man to wear a tayshaxı."

|

This page was first published on 11 March 2007. It was last updated on 8 February 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2015. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |