The Karakalpak Kiymeshek - Part 1

|

The Karakalpak Kiymeshek - Part 1

|

|

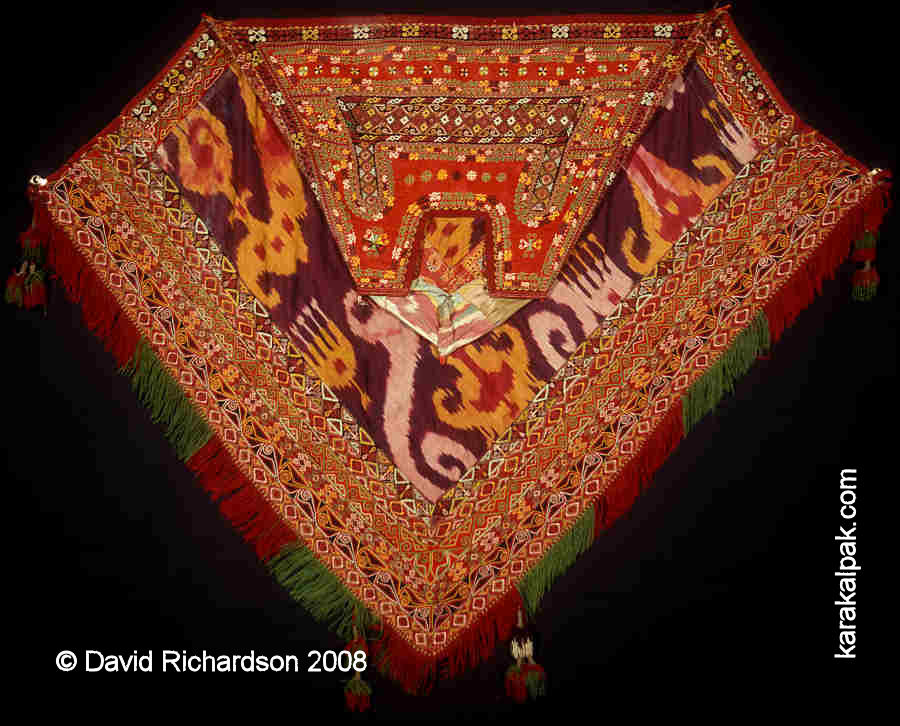

ContentsPart 1SummaryThe Karakalpak Kiymeshek Role of the Kiymeshek The Aq Kiymeshek The Qızıl Kiymeshek Part 2Different Qızıl Kiymeshek PatternsDistribution of Qızıl Kiymeshek Patterns The Dating of Qızıl Kiymesheks Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms References Part 3Other Kimeshek-Like GarmentsThe Qazaq Kimeshek The Uzbek Lyachek The Tajik Lachek and Kuluta The Turkmen Esgi, Lechek and Chember The Kyrgyz Elechek and Ileki The Khimar and Similar Islamic Veils References Part 4Previous Ideas on Kimeshek OriginsA Short History of Veiling up to the 16th Century References Part 5The History of the KimeshekWhere to see Karakalpak Kiymesheks References SummaryThe Karakalpak kiymeshek is a woman's head veil, which covers the hair and uppermost part of the body but leaves the face exposed. It was always worn with a matching turban. It is an integral garment, immediately recognizable by its embroidered triangular front and its diamond-shaped shawl at the back.

Schematic layout of a Karakalpak qızıl kiymeshek.

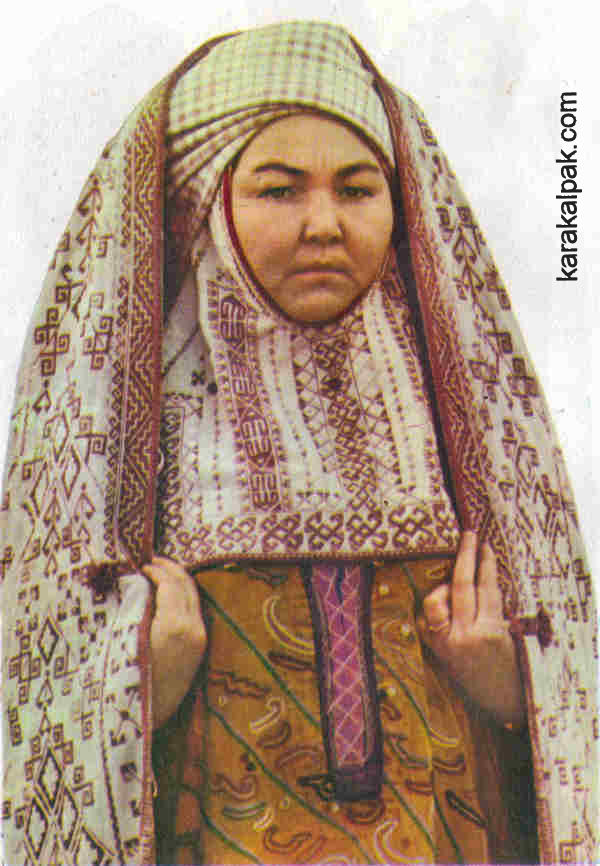

Kiymesheks were not worn every day, but only for weddings and other formal or festival occasions. This is why so many have been preserved for posterity. Kiymeshek -like garments were also worn by the Qazaqs, Uzbeks, Tajiks, and even some of the Turkmen. They may also once have been worn by the Kyrgyz. The kiymeshek emerged simultaneously in Persia and Central Asia during the first half of the 16th century. It had evolved from an earlier headdress of similar appearance that was formed from a simple rectangular-shaped shawl. This was wrapped across the breast and over the head so that one end fell down the back. Such headdresses date from at least the 7th century. In Arabia they were known as a khimar and are referred to in the Qu'ran. The dispersal of the kimeshek into the nomadic populations of Central Asia is only partly associated with the adoption of Islam and more likely reflects the gradual spread of urban materials and fashions into the steppes during the 18th and 19th centuries. Of course the practice of covering a bride's hair at the time of her wedding is an ancient ritual frequently recorded throughout antiquity in both the Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. Its origins probably lie in the mists of pre-history. The Karakalpak KiymeshekThe Karakalpak kiymeshek (written киймешек in Karakalpak) is one of the most striking and unusual garments to come out of Central Asia. It is a sleeveless woman's cloak or cowl, worn over the head, veiling the hair, neck, shoulders, upper breast, and back. The kiymeshek was always worn with a matching oramal or turban, made from one or more scarves and kerchiefs. Outside of her home a woman wore a matching jegde cloak above both the kiymeshek and the oramal.There are two fundamentally different types of kiymeshek, both of which were only worn by married women. The white aq kiymeshek was worn by the elderly and the red qızıl kiymeshek by younger women.

An aq kiymeshek (above) and a qızıl kiymeshek (below),

each worn with a matching oramal and jegde.

|

|

Kiymesheks are mainly but not exclusively associated with the Karakalpaks from the northern part of Khorezm, the fishing and

cattle-breeding tribes belonging to the Qon'ırat arıs or division, rather than with Karakalpaks from the more southerly

dwelling On-To'rt-Urıw arıs, who were more intensively engaged in irrigated agriculture. However they were also worn by other

populations within the Karakalpak diaspora, such as those living in the Ka'nimex region just north of Navoi. A special study of the Karakalpaks

living in the Samarkand region, conducted by L. S. Tolstova and the Karakalpak branch of the Uzbek Academy of Sciences in 1960, discovered that

old women remembered wearing an embroidered red kiymeshek in their younger days.

In the last decades of the 19th century and up to the 1930s, the qızıl kiymeshek was a key component of the female

wedding costume. After the wedding the same costume was worn for major festivals and important ceremonial events. The kiymeshek was

therefore never used for daily wear. This occasional use explains why so many kiymesheks have survived the rigours of Karakalpak

ownership in such good condition.

The kiymeshek is the one garment that expresses the exuberance and uniqueness of Karakalpak material culture. It is also the most

common item of Karakalpak costume likely to be found in overseas textile collections. The closest European analogy is the medieval wimple worn

under a veil, which dates from the 12th century.

Role of the Kiymeshek

As already mentioned, there are two different categories of kiymeshek: the white aq kiymeshek and the red qızıl

kiymeshek.

Numerous interviews with old Karakalpak people conducted by ethnographers throughout the Aral delta from the 1950s onwards have established a

good picture of how these two types of kiymeshek were used in the early part of the 20th century. Nina Lobacheva, who as part of the

Khorezm Archaeological and Ethnographic Expedition was responsible for research on Karakalpak costume, finally published some of her earlier

field results in 2000. This research was conducted in the Kegeyli, Shımbay, Taxta Ko'pir, Qarao'zek, Qon'ırat and Moynaq districts

of Karakalpakia and on the islands of Tazbesqum, Mergenataw, Qaraboyly, and Qaradjar on the southern coast of the Aral Sea. Our own discussions

with elderly Karakalpaks during recent years are consistent with these findings.

In short the qızıl kiymeshek was worn by younger married women and the aq kiymeshek was worn by older women.

However, this may not have been the case during the 19th century see below.

|

The qızıl kiymeshek was an important part of a girl's traditional wedding dowry. Embroidery and weaving

were considered essential female skills and since girls were often married by the age of 15, they were taught from an early age. By the age of

6 or 7 they could have already begun preparing their wedding dowry, assisted by older female friends and relatives. A young girl was expected

to weave tent bands for her future yurt and to assemble five key items of wedding costume, known as the bes kiyim. This consisted of a

qızıl kiymeshek, ko'ylek, qızıl jegde, qızıl tu'rme, and a pair of

zerlı gewish overshoes. The first three of these items were prepared by the girl herself, although the tu'rme was purchased from

the bazaar, the shoes being commissioned from the local cobbler. The qızıl kiymeshek was the star item in her dowry and

she would begin its preparation with a prayer. In addition, a girl might also embroider an aq kiymeshek or an aq jegde as a gift

for her future mother-in-law, especially if she came from a rich family.

|

In the past the marriage was usually arranged, probably having been negotiated between the parents of the bride and groom some years before the

wedding. In extreme cases, the marriage may have been agreed while the girl was still in the cradle. This agreement between the two sets of

parents signified the engagement. Of course, the wedding itself could not occur until the payment of the qalın' to the bride's

parents as compensation for the loss of her services, this being the necessary condition for the marriage to be concluded. After this the bride

could move to her husband's village and begin life as a married woman.

At the time of the Russian invasion in 1873 Karakalpaks married at a very early age. According to Sobolyev males were married at the age of 15

and girls between the ages of 12 to 15. The Russians exerted pressure on the Karakalpaks to raise the age of marriage for girls, but the regulations

and procedures were frequently circumvented. In 1902 Rossikova discovered cases of Uzbek girls being married at the age of ten or eleven, although

these were exceptions.

The final wedding ritual was often a two- or three-day affair, commencing on an auspicious day such as a Wednesday. It began at the home of the

bride's parents and later moved to the home of the groom's parents. The actual rite of marriage or neke qıyıw occurred in

the home of the bride's parents. At the end of the first or on the second day the young bride would say goodbye to her family and friends and,

with the accompaniment of special farewell songs, would depart in a donkey cart for her new husband's village. Before leaving her home she was

dressed for the wedding in everything but her qızıl kiymeshek by her tutor, or qız jen'ge, normally the

wife of her elder brother or the wife of an uncle on her mother's side. At the same time her hairstyle was changed from that of a girl to that

of a married woman, her maidenly temple plaits being undone so that her hair was gathered into just two long rear plaits. Thus she departed as

a married woman wearing her ko'ylek, ha'ykel, shapan, jegde, and zerlı gewish.

The bride only donned her qızıl kiymeshek later, assisted by her proxy mother, or murındıq ene, a

female relative from the groom's side of the family (or from the groom's village) who had been selected to act as her new mentor and advisor from

now on. As explained by Nina Lobacheva, the Karakalpaks interviewed during the 1950s did not always agree about the exact moment when this occurred.

Some informants suggested it was when the wedding group stopped along the way, others that it took place on the arba (cart) on the edge

of the groom's village, others that it occurred outside of the groom's home, and others that it happened on the actual threshold of her father-in-law's

home. However, with just one exception, all agreed that it took place before she entered the home of her future in-laws. The dissident view was

expressed by a member of the U'shtamg'alı clan from Qon'ırat region in 1959, who claimed that the qızıl kiymeshek

was not worn until a married woman was around 25-years-old and had borne her second child. However this was the normal practice of Uzbeks with the

somewhat similar lyachek, and may have been copied from the many Uzbeks who live in the Qon'ırat region.

Every single hair on the bride's head had to be hidden under the qızıl kiymeshek. The cap of the kiymeshek was

concealed by a bas oramal or turban, made from a qızıl tu'rme, above which the bride wore a qızıl

jegde. She entered her future father-in-law's home with her face hidden.

|

The main wedding feast or u'yleniw-toy (or uly-toy) took place at her new father-in-law's home later that evening or on

the following day. During the celebrations the bride remained out of view in her kiymeshek, hidden behind the

shımıldıq wedding curtain. Only later was the bride presented to the husband's family and village dressed in her

wedding finery, her face covered by a white veil. After a short speech by a respected male elder, her face was revealed to the crowd, a ritual

known as the bet ashar (discovering the face). The bride would then present gifts to the village elders and youngsters within her new

village. Later a mullah would bless the couple. If she were lucky she and her groom would spend their wedding night in a bridal yurt,

or otaw, provided by his parents but decorated with weavings from her dowry. Otherwise she would sleep with the rest of her new family.

A bride was expected to wear the kiymeshek for as long as possible after the wedding. One woman interviewed by the Khorezm Ethnographic

Expedition in the 1950s said that she wore hers for as long as a month and thereafter donned it only for special occasions other weddings,

circumcision celebrations, Nawrız, Ramazan Bayram (the end of Ramadan), Qurban Bayram (the festival of sacrifice, 70 days

later) and Paxta Bayram (the cotton harvest festival). Most of the qızıl kiymesheks in museum and private collections

are in fairly good condition, suggesting that they were only worn intermittently, even though some show evidence of repair, including the replacement

of the vulnerable quyrıq. None shows the level of wear one would expect from continuous usage.

At the end of a woman's childbearing years her festival costume would be changed to the more conservative attire of the older woman. She would cease to

wear the qızıl kiymeshek, qızıl tu'rme, and qızıl jegde in favour of the

aq kiymeshek, aq tu'rme, and aq jegde.

|

However the qızıl kiymeshek could not be discarded. A woman was expected to keep such an important item in the

sandıq, since at the time of her funeral this would be displayed to all of her relatives and neighbours, suspended from a tent band

along with her jewellery and other decorative items. Women believed that the mullah would not read their final prayer - the jan'aza

or prayer for the dead - if important parts of their costume were missing. It was also customary for the women who washed her body before the

funeral to take a small souvenir.

As we shall see later the fashion for wearing the qızıl kiymeshek began to wane in the late 1920s, possibly in response

to the increasing availability of cheap and colourful Russian manufactured kerchiefs. By the mid-1930s it had been replaced by the oramal

turban and a kerchief head veil.

In 1984 Nina Lobacheva suggested that prior to the development of the qızıl kiymeshek (in the late 19th century), the

aq kiymeshek may have served the same function - namely as the wedding costume of the Karakalpak bride. Her argument was based upon the fact

that its embroidery was predominantly red in colour the colour normally associated with the costume of young women. With the emergence of the

qızıl kiymeshek, the role of the aq kiymeshek gradually changed from being a married woman's garment to a festival

costume for older women. Of course one could equally argue that the colour white has traditionally been associated with the elderly. The main

evidence supporting Lobacheva's theory is the observation by Arminius Vambery in 1863 that Karakalpak women wore a cape like a cloak around the throat.

Though brief his comment seems to refer to women in general, not those of advanced age see The History

of the Kimeshek.

Kiymesheks are associated with an ancient belief that a woman's hair was potentially dangerous and provided a conduit for evil forces

to enter her body and mind with the intention of damaging her, her fertility, her unborn child, and perhaps even those around her. In the past

people across Central Asia were concerned that their hair should not fall into the hands of ill-wishers. For example hair that had fallen out

during the process of washing was hidden in the cracks of the clay walls of the house or buried under the threshold of the yurt. Consequently, by

concealing the hair, a kiymeshek offered a woman protection from harm, especially when she was particularly vulnerable during her

marriage and later childbearing years. Only complete one hundred percent coverage guaranteed her safety.

Karakalpak kiymesheks also provided amuletic protection for the wearer. For example they were always decorated with red which was believed

to have protective powers against the evil eye. Red was the most common colour for the clothing of girls and younger women throughout Central Asia.

Indeed the protective force of a kiymeshek was so powerful that it was sometimes used to protect or assist other family members. For

example Anna Morozova noted that old kiymesheks were cut up and used to make kurte, or overshirts for small children, thereby

shielding them from danger. If there was an illness in the family a section might be cut out of a kiymeshek and burnt to facilitate a

cure, while when an old woman died her kiymeshek was cut up and distributed to the surviving family members. If the woman had lived to a

ripe old age her relatives would benefit from her longevity.

The Aq Kiymeshek

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries women aged 60 years or older wore aq kiymesheks, although there are occasional references to

women wearing them in their 40s. Most of Lobacheva's informants suggested that the aq kiymeshek was worn at the age of 60, 65, or 70

years, only one source suggesting it was worn by women as young as 40. They were not items of everyday wear, being kept for special occasions.

Aq kiymesheks are relatively rare compared to qızıl kiymesheks: even in the 1950s Russian ethnographers found

them hard to come by. From our own experience one encounters one aq kiymeshek for every five qızıl kiymesheks.

However we may have been lucky the Savitsky Art Museum in No'kis holds 336 qızıl kiymesheks and

qızıl kiymeshek aldıs, but only 36 aq kiymesheks and aq kiymeshek aldıs, while the equivalent

figures for the Regional Studies Museum are 164 and 5. Adding the two museum inventories together one obtains a ratio of over twelve

qızıl kiymesheks for every one aq kiymeshek.

Furthermore it is nearly impossible to find a complete aq kiymeshek garment there are just two examples in No'kis, one in the Savitsky

Art Museum and one in the Regional Studies Museum, and two in the Richardson collection in England.

|

|

If a family still keeps an aq kiymeshek as an heirloom, they are likely to have only the aldı. This is because it was

common for an old woman's kiymeshek to be cut up following her death so that the pieces could be distributed among her family. As

already mentioned if the woman was very old people believed that the new owners of these fragments would also enjoy a long life. However the

aldı was generally kept intact and passed to the eldest member of the following generation, although we have found some exceptions

to this rule, where even the aldı was cut into pieces.

|

Although there are some pristine examples of aq kiymesheks in museum collections, the overwhelming majority encountered in the field are in

considerably worse condition than corresponding qızıl kiymesheks. Because of this it seems clear to us that they generally

date from an earlier period.

The relative scarcity of aq kiymesheks may be partly because they went out of use earlier than the qızıl kiymeshek,

so many have not survived, and partly because they were not universally worn by old women. When ethnographers from the Khorezm Expedition interviewed

old people in the 1950s they were told that aq kiymesheks were only worn for special occasions, as we have already noted. However some of

these old people claimed that aq kiymesheks were only found in rich families, although this may relate back to a time when they were already

going out of fashion. They were usually worn with an oramal or turban of either plain white cotton or pink-checked white cotton boz,

and more rarely with a turban made from a folded silk aq tur'me. If an old woman left her home she would cover her kiymeshek and

turban with an unlined aq jegde cloak.

|

Traditionally aq kiymesheks were made from handwoven off-white cotton (bo'z), although later examples employed imported machine-made

cotton and, as we have seen above, even damask. The off-white cream colour was achieved by dyeing the cotton using the ju'weri plant, a type

of local cereal somewhat similar to wheat. The cotton used for the aldı was often quite coarse and of double thickness. The grid-like

structure of its weave facilitated its decoration with a geometric pattern of cross-stitch embroidery using mainly raspberry red and cream silk threads,

although varying amounts of other colours such as pink, golden yellow, or green were also incorporated.

|

The Karakalpak term for cross-stitch is shırısh tigiw. Note that chain-stitch embroidery was never used on the bo'z

face of the aq kiymeshek aldı.

All of the outer edges of the aldı, including the face opening, were generally finished in raspberry red jiyek, a braid-like

edging that was woven directly onto the garment by hand using the technique of loop manipulation. The back (artqı) or tail

(quyrıq) was left undecorated, although its outer edges were also bordered with jiyek, or alternatively a piping of red cotton.

Its two lower edges were finished with a fringe of alternating red and cream or red and yellow tassels.

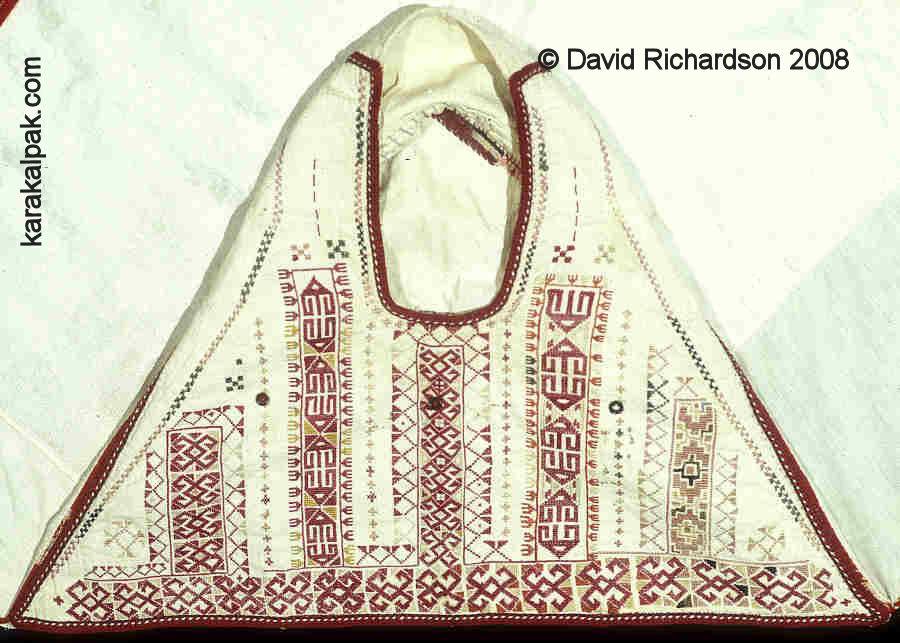

In recent years we have spent some time analysing the structure and design of aq kiymesheks in both museum and private collections. From this

work it is clear that the same basic decorative layout was used on virtually all aq kiymeshek aldıs: a single horizontal row of cross-stitch embroidery motifs run along the base of the aldı, while a number of vertical columns of cross-stitch embroidery motifs rise

above it. The number of columns is always an odd number, one column being placed centrally under the face opening, the others being arranged on either

side in decreasing height. Sometimes further embroidery details appear in the corners, along the two sloping sides or at the top.

The number of vertical columns varies from three up to eleven. Out of a sample of 32 aq kiymeshek aldıs 14 had seven columns, 13

had five, 2 had nine, one had none, one had three, and one had eleven. Although the same motif is always repeated within each column the majority of

aq kiymeshek aldıs include a number of different motifs, creating vertical columns of different appearance. In 85% of cases these

are arranged symmetrically around the central column, but in 15% of cases they are arranged asymmetrically, different motifs being used on each side.

In 75% of cases the motif used in the horizontal row is also the motif used in the central column, and often in the columns on each side of the

three central columns.

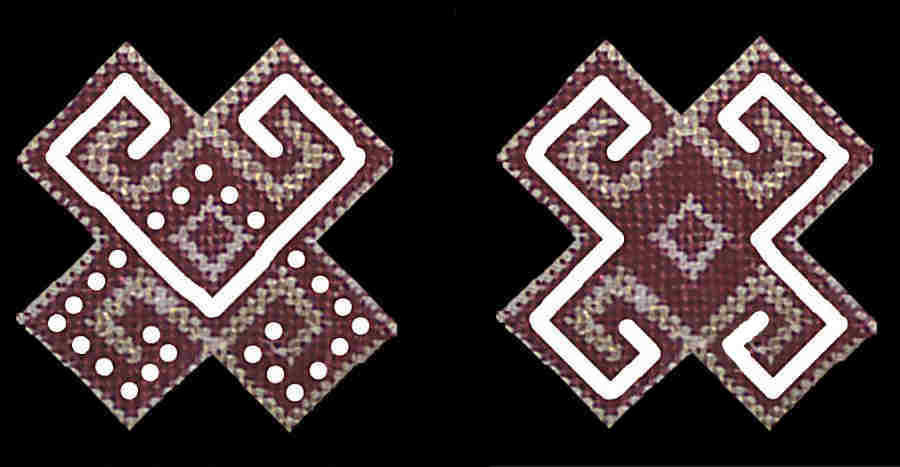

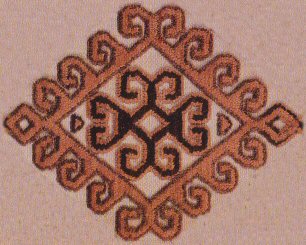

The most frequently occurring cross-stitch motif in aq kiymeshek aldıs is the crossed horns or Xorosanı mu'yiz motif:

|

This was frequently used in other examples of cross-stitch embroidery, such as on aq jegdes, ko'k ko'yleks , and jen'se.

It name relates to the horns of cattle from Khurasan. Ag'ınbay Allamuratov used the clumsy term

qoltıqsha mu'yiz, meaning armpit horns, because the motif was often embroidered close to the underarms of jegdes. The motif can be viewed in two alternative orientations in one it appears as two crossed pairs

of inward facing horns, in the other it appears as two pairs of opposing or outward facing horns, separated by a small diamond:

|

The Xorosanı mu'yiz motif occurs in 85% of aq kiymesheks. In 69% it forms the main horizontal decorative band and in 53% it forms both the

horizontal band and the central vertical column. Other horn motifs such as segiz mu'yiz (eight-horns), or on yeki mu'yiz

(twelve horns), are occasionally used instead.

The second motif most likely to be encountered in aq kiymesheks is the diamond or lozenge containing a central cross. Given the geometric

nature of cross-stitch embroidery, the outer diamond is sometimes depicted with stepped sides. Karakalpaks refer to this motif as the

at ayıl nagıs, or horse's bellyband pattern, because it is always used on saddle belts. It occurs in 38% of our sample of 32

kiymesheks, and forms the horizontal band in 16%.

Out of our sample of 32 aq kiymesheks 40% are finished with just a narrow edging of raspberry red silk jiyek. The remaining 60% are

edged more elaborately, with a partial outer border of red cloth, and in a minority of cases 19% - red and black cloth. In almost all cases, this

red and black cloth is the felted woollen textile ushıga. Of this remaining 60%, 40% have varying amounts of chain-stitch embroidery

on the ushıga border. Once again the cloth border is edged with jiyek, generally of a red colour, but sometimes a light

yellow, or even with an integral pattern.

In many cases, these outer cloth borders appear to have been a later addition, as a result of a new border being given to an older

aq kiymeshek aldı. In some examples this is obvious in one the surrounding cloth border has been decorated with machine-stitched

embroidery, which was only possible in Karakalpakia from the 1920s onwards; in others the cross-stitch embroidery is many decades older than

the chain-stitch embroidery. However there are other examples where the cross-stitch and the chain-stitch appear to be of similar condition and age.

It is hard to classify aq kiymesheks into separate design groupings. There were only a few rules: the embroidery had to be cross-stitch

on the bo'z, there had to be a lower horizontal band, and above this an odd number of columns. The Xorosanı mu'yiz motif was preferred but

not obligatory. Within this rather open framework the embroiderer used her imagination to combine a selection of geometric and zoomorphic motifs

to create a unique and stunningly beautiful garment. Every example was different.

There seems to be a continuous spectrum of designs, ranging from simple to complex. The simplest designs tend to be the most elegant, with just

raspberry red and cream embroidery, five or at most seven vertical columns, and a simple outer edging of either jiyek or plain or printed

red cotton.

|

|

|

The more complex designs have a higher density of embroidery and a greater use of green and other coloured threads. It is interesting that

aq kiymesheks containing green threads are more likely to have a red, or less frequently red and black, outer border of ushıga.

|

|

|

One might theorize that the simplest designs are the earliest and that, as with many other ethnic textiles, increasing complexity has evolved over

time. Certainly Ayg'ul Pirnazarova, the Curator of Costume and Jewellery at the Savitsky Museum, believes this to be the case. She thinks

that the earliest designs used just red and cream embroidery threads and that the addition of green and other colours occurred much later.

However there seems to be no correlation between a design and the apparent age inferred from its physical condition. Indeed some

aq kiymesheks with the simpler designs appear to be more recent than those with more complex designs. Of course this may simply be

down to how the garments were cared for during their lifetime.

Unfortunately it has not been possible to date a single Karakalpak aq kiymeshek. Those in museums have insufficient provenance, while

the owners of those encountered in the field have insufficient knowledge of their history. By contrast the owners of

qızıl kiymesheks do generally know their history (dealers excepted), from which one can perhaps infer that aq kiymesheks

date from an earlier era.

The Qızıl Kiymeshek

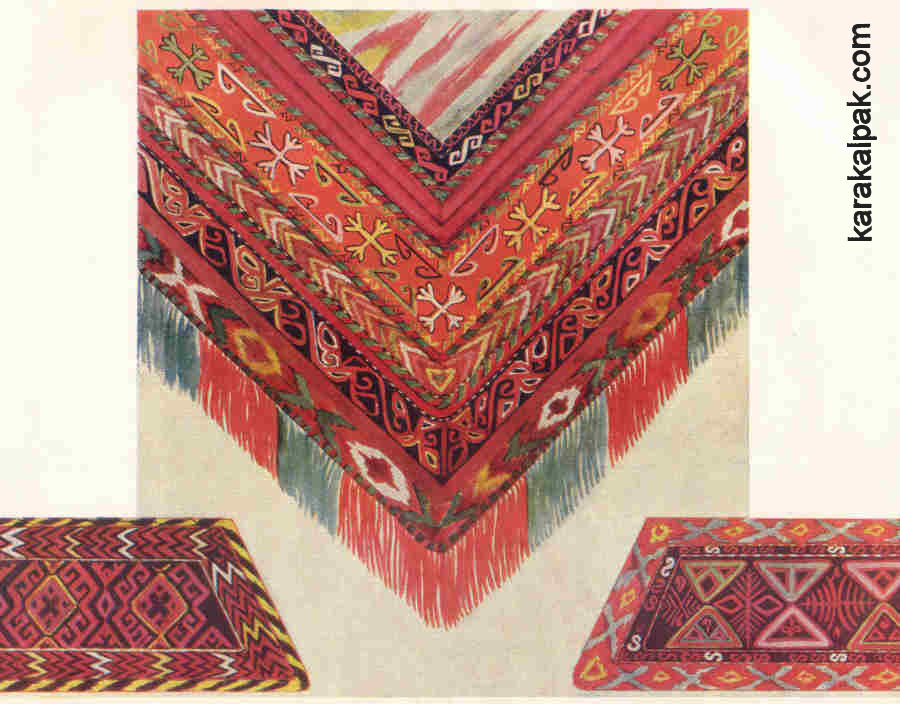

The qızıl kiymeshek is a more complex and more visually stunning garment than the aq kiymeshek. It was primarily

red in colour, richly decorated with a wider colour palette of silk threads, had a larger aldı and a much bigger

quyrıq that hung down to the calves and was edged with an embroidered and fringed border.

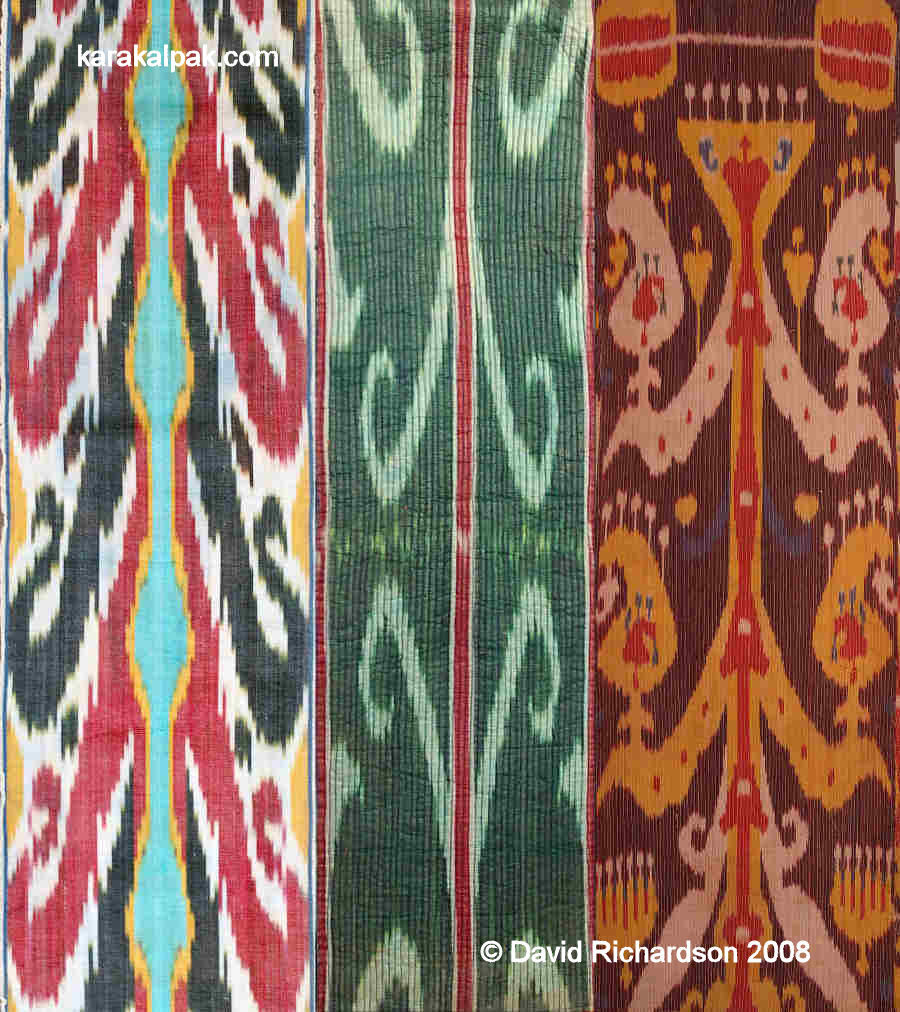

Qızıl kiymesheks were never made from homemade bo'z but from three quite different and more exotic imported fabrics:

|

Some authors have claimed that 100% silk shayı (referred to as shoyi in Khiva, meaning kingly) was also used for the

production of kiymesheks. However we have never encountered a single example made from shayı, not surprising because

it is simply not strong enough for the job. The qızıl kiymeshek contains a fundamental design fault the silk

quyrıq is simply not strong enough to support its heavy embroidered border. As a result even the stronger

pashshayı, (meaning sub-shayı), which is clearly recognizable by its finely ribbed structure, tends to tear

over time.

|

A minority of qızıl kiymesheks do incorporate Bukharan rather than Khorezmian ikat adras, which is recognizable

by its much larger width and wider variety of patterns.

|

Despite references to the use of woollen or red velvet textiles in place of silk ikat

we have only ever seen two or three examples of this type and these were all the result of much later restoration. In a few rare cases the

adras is lined with printed cotton.

|

Because the quyrıq is so vulnerable to tearing, the adras in many kiymesheks has often been replaced. In some

cases the owners have used traditional ikat adras from old ko'yleks, shapans, or in one case from the lining of an Uzbek

paranja; in others they have used the quyrıqs from other kiymesheks. One also occasionally comes across the

use of machine-printed silk or even printed cotton faux-ikat, a later and much cheaper alternative to pashshayı.

In recent years the situation has become confused with unscrupulous dealers combining the parts of different kiymesheks to make up

complete garments.

The majority of qızıl kiymeshek aldıs and the borders of the quyrıqs were lined with scraps of

machine-printed cotton, which was imported from Russia in increasing quantities from the late 19th century onwards. The most frequently

occurring cotton lining is a rather dull multi-coloured stripe, which crops up in about 90% of kiymesheks.

It was the availability of all of these new imported fabrics which inspired the creation of the Karakalpak qızıl kiymeshek.

In particular the smooth felted surface of the woollen ushıga was quite unsuitable for geometric cross-stitch embroidery, so

early qızıl kiymesheks were decorated with a horizontal band of cross-stitch, embroidered on a strip of chequered cotton

shatırash, some of which was imported from Nurata. In time the nature of the fabric encouraged the alternative use of chain-stitch,

known in Karakalpak as shınjır tigis. This resulted in the introduction of a completely new set of free-flowing floral

and zoomorphic motifs, creating a completely different style of kiymeshek.

|

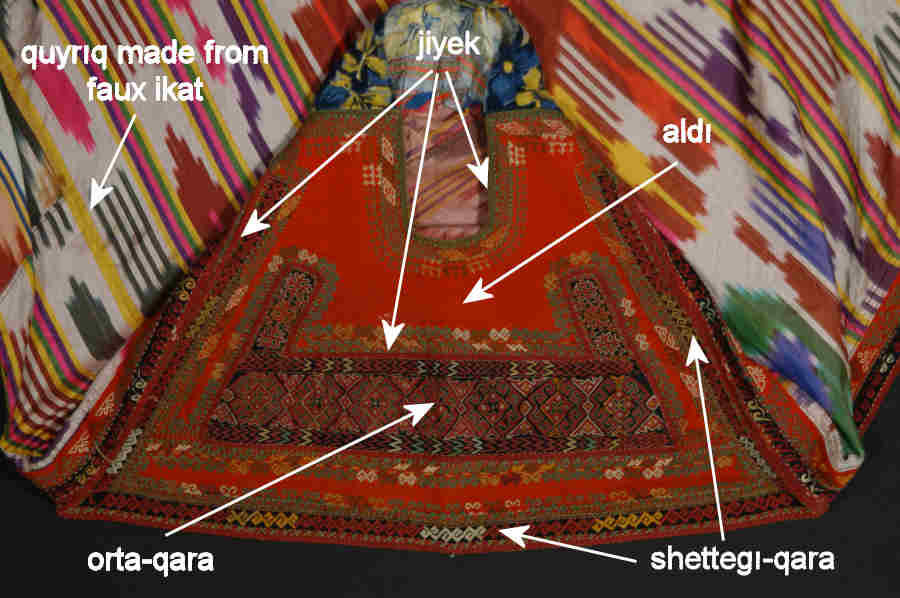

The component parts of the qızıl kiymeshek were defined by Allamuratov in 1977. The qızıl kiymeshek

aldı consisted of a truncated triangle made up from one or several pieces of qızıl ushıga, edged

at the sides and bottom with a narrow border of qara ushıga. The latter was known as the shettegı qara or

edge black. A wider vertical strip of qara ushıga was sewn centrally below the face opening, and smaller strips were placed at

each end extending upward, parallel to the sloping sides of the aldı. This feature was called the orta qara or middle

black. Sometimes a narrow strip of qara ushıga was used to border the face opening. Generally the divisions between the red

and black ushıga were edged with raspberry red jiyek, as were the outer edges of the aldı, woven in

situ using loop manipulation. Sometimes this jiyek was overembroidered with diamond and cross patterns in silk of different colours.

In some kiymesheks green or patterned jiyek was applied around the face opening and along the top of the aldı.

|

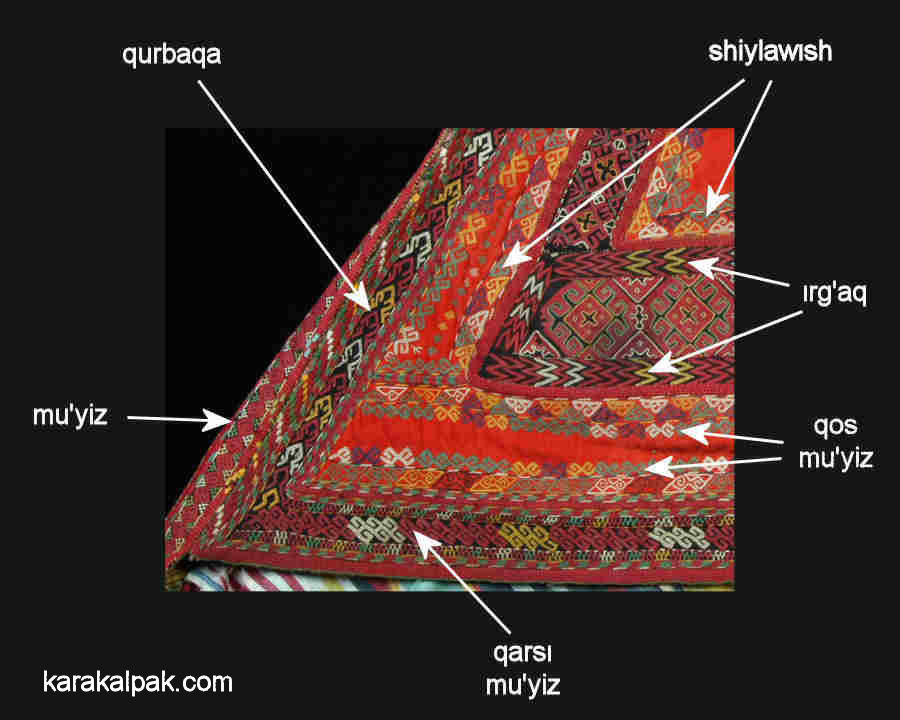

The majority of qızıl kiymesheks were intensively decorated with a plethora of motifs embroidered using a wide range of

coloured silk threads, mainly red, green, yellow, black, and white. A minority include small amounts of gold thread work and are known as

zer kiymesheks. For the aldı the main pattern incorporated within the orta qara was always very distinctive

and, as we shall see below, fell into one of a limited number of types. The shettegı qara was generally embroidered with one or

more rows of simple repetitive motifs, as were the edges of the qızıl ushıga bordering the

shettegı qara and the orta qara. The most common border patterns were qos mu'yiz (double horns),

qarsı mu'yiz (countervailing horns), qumırısqa bel (the waist of an ant), shiylawısh (a

wood plane) and solaq (the fastening hook of a cart). Further adornment sometimes occurred in the form of additional metal platelets,

buttons, coins, beads, seeds, bells, pendants, and even fur.

|

The quyrıq was made from lengths of ikat adras sewn together side by side to form a square. This was then edged with

a heavy border composed of an inner strip of qızıl ushıga and an outer strip of qara ushıga,

both embroidered with rows of motifs in chain-stitch. Some of the finest quyrıqs are made from three or even four separate

alternating strips, often separated by borders of jiyek. These ushıga borders, especially the two lower ones, were

generally embroidered with bold motifs such as tu'ye taban (camel's foot), qurbaqa (frog), sırg'a nag'ıs

(earring motif), or quwırshaq awız (doll's mouth). The two lower edges of the quyrıq were finished

with a long fringe of alternating blocks of red and green twisted silk tassels, sometimes with occasional longer suspensions of tassel clusters.

|

The quyrıq of the qızıl kiymeshek is much larger than that of the aq kiymeshek, about one metre

square in size. When worn the lower corner of the qızıl kiymeshek almost reaches the ground. The quyrıq

was occasionally connected to the aldı by an additional strip of qara ushıga known as the iyin qara, or

shoulder black. However in some examples this was just a plain strip of ushıga or some other textile.

Visit our sister site www.qaraqalpaq.com, which uses the correct transliteration, Qaraqalpaq, rather than the

Russian transliteration, Karakalpak.

|

This site was first published on 7 March 2008. It was last updated on 5 February 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2015. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |