|

Location

The remains of Devkesken qala and the old city of Vazir lie 101km west of No'kis and 62km west of Kunya Urgench in the Dashoguz welayat of

northern Turkmenistan. They are situated at the south-western corner of a 30 or 40km-long finger-shaped peninsula of the Ustyurt plateau that projects

out into the Qara Qum desert, almost reaching the dried-out channel of the old western arm of the Amu Darya that used to run into the Sarykamysh Lake.

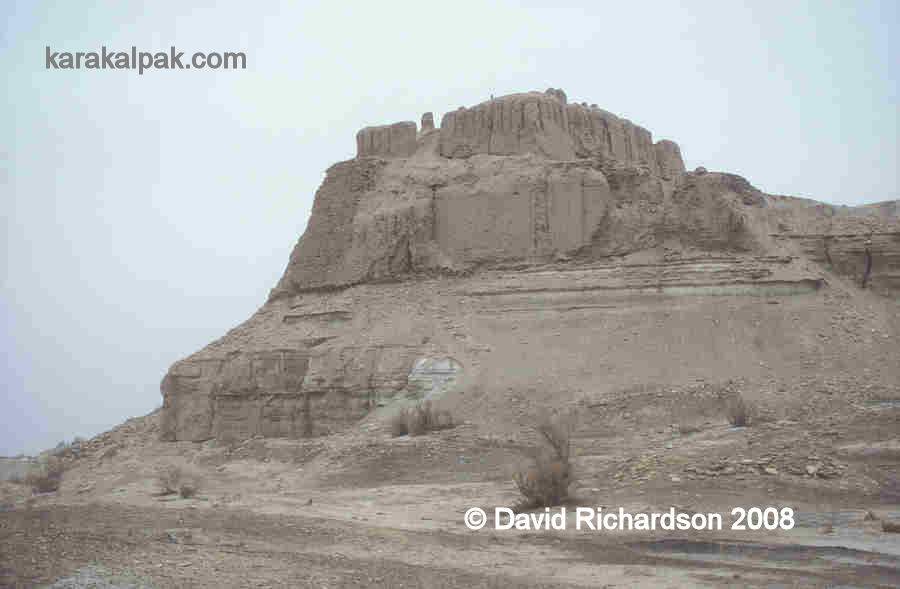

Today the course of the Darya Lyk flows 13km to the south of Devkesken qala. The qala, a medieval mosque and two mausoleums are dramatically located

on the edge of the cliff edge or tchink of the Ustyurt plateau. The elevated square-shaped fort can be seen from a distance of 20km. Part of

the excitement of visiting Devkesken is the journey through the bleak and empty desert wilderness that surrounds it.

Devkesken qala overlooking the barren Qara Qum.

The ruins can only be reached by leaving the main highway and crossing a section of the Qara Qum using a 4WD vehicle. We recommend hiring an

experienced driver who knows where to cross the irrigation canals that block the way. There is a small Turkmen army garrison close to the site since

this is a sensitive area where the border between Karakalpakstan and Turkmenistan is still disputed. Tourists must report to the garrison and deposit

their passports and are then assigned their own personal soldier to oversee their visit to the site. The officers are sensitive to any photography.

However for your minder this is a welcome break from his usual daily routine of mind-numbing monotony. If you are friendly and diplomatic you should

be able to get away with a few shots.

Foreign tourists can cross the Karakalpak-Turkmen border checkpoint between Xojeli and Kunya Urgench, but must be in possession of a Turkmenistan visa.

See the "How to Get There" page of our

Tour Guide.

Excavations

Sergey Tolstov and his Khorezm Archaeological-Ethnographical Expedition first investigated Devkesken in September 1946, identifying the surrounding

ruins as the ancient town of Vazir. In October 1947 Tolstov used the Qara Qum at Devkesken as a base for conducting an aerial survey of the surrounding

region and the Uzboy valley.

One of Tolstov's bi-planes overflying Devkesken in 1947.

Devkesken was surveyed and investigated in more detail by E. Bizhanov in 1963 and 1964. His excavations made it possible to establish a schematic

history of the sites development.

Further work was conducted in the mid 1980s by Vadim Yagodin and G'ayratdiyin Xojaniyazov of the Karakalpak Branch of the Academy of Sciences in No'kis.

Xojaniyazov and Khakiminiyazov published additional findings in 1997 concerning both the antique fortifications and the late medieval town.

Devkesken qala and Vazir

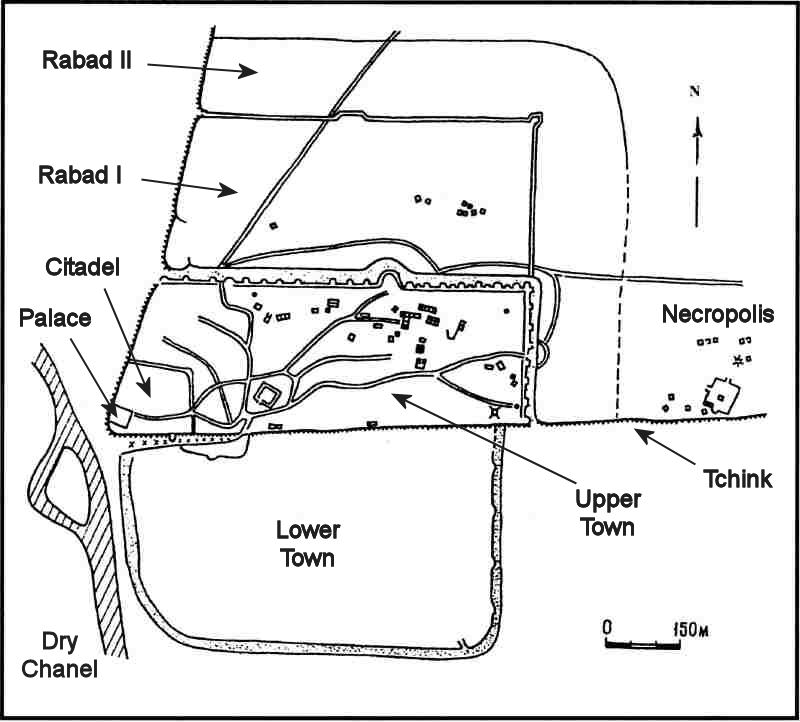

The archaeological complex of Vazir extends for about 1 kilometre from east to west and for about 1¼ kilometre from north to south. It contains

a number of separate parts but is probably best understood in terms of an upper town and a lower town.

Poor quality satellite image of Devkesken and Vazir. Image courtesy of Google Earth.

Note the s-shaped channel of the old watercourse.

Plan of Devkesken and Vazir. From Xojaniyazov, 2006.

The upper town is situated on the cliff tops, some 30 metres above the surrounding plain, at a triangular cape of the Ustyurt plateau. It has a narrow

trapezoidal shape, 850 metres long and 300 metres wide, with its south and west sides protected by the abrupt cliff face of the Ustyurt, known as the

tchink, and with its north and east sides defended by massive walls, the ends of which reached close to the cliff edge. The walls, which even

today reach some 5 to 8 metres in height, were reinforced by regularly spaced rectangular towers and one unusual large semicircular tower. Additional

protection was provided by an outer ditch some 10 metres wide and 3 metres deep. The entrance to the town was in the middle of the eastern wall,

defended by two flanking towers.

Aerial view of Devkesken from the east, clearly showing the separate parts of the city, the s-shaped

river channel and the Timurid garden beyond. Image from Tolstov's 1947 survey.

Aerial view of Devkesken from the south west, clearly showing the palace and citadel on the point of the cape,

the upper and lower towns and the grid-like park in the foreground. Image from Tolstov's 1947 survey.

The partial remains of a southern defensive wall have also been discovered along the top edge of the tchink, along with a rounded tower and a

second gate. The cliff edge is very unstable at this point and most of the wall has probably subsided. An inclined ramp, which appears to be based

upon a natural feature, runs along the face of the tchink up to the location of the southern gateway. Within the upper town there was a

fan-shaped system of roads, at least three wells and one underground dwelling.

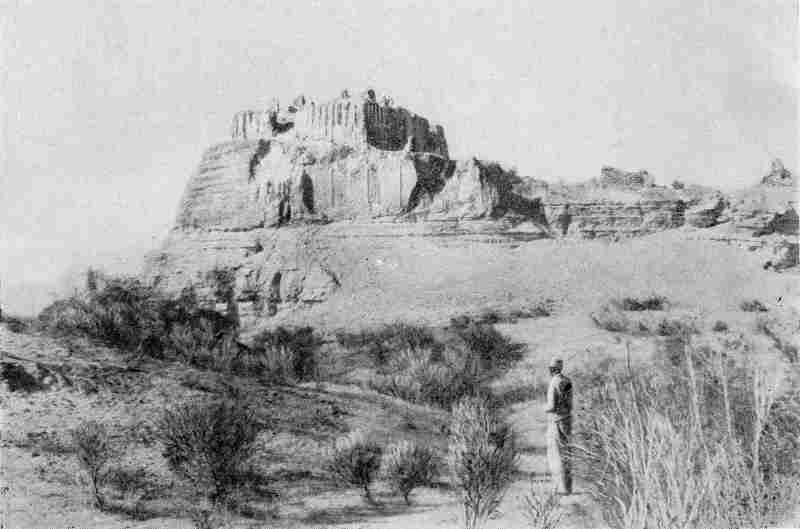

View of the citadel and fortified palace from the south.

In the far south-west corner of the upper town there is a rectangular citadel, roughly 100 by 75 metres in size, with an entrance in the middle of its

eastern wall. Within this citadel, positioned right on the corner of the tchink, is a small fortified "palace", built of unfired mud brick

with the upper parts of its windowless walls decorated with fluted pilasters. It almost looks like a natural part of the landscape. This is Devkesken

or Dev Kesken qala, a local name that means the "castle carved out by demons", a very appropriate description.

Devkesken qala, the castle carved by demons.

Devkesken qala from below. That such a small and simple building should be the

palace of a Khorezmshah gives some indication of the state of Khorezm in the early 16th century.

Devkesken qala in 1946 or 1947.

To the north of the upper town is a second similarly shaped trapezoidal enclosure, the rabad or new town, with the tchink forming

its western boundary and another defensive wall protecting its northern and eastern sides. The upper town and rabad are then enclosed to the

north and east by a second, presumably later L-shaped rabad or suburb. Just outside the eastern wall of this suburb, close to the edge of the

tchink, are the town necropolis and the remains of an iron foundry.

The unnamed mosque at Devkesken.

The lower town is situated just below and to the south of the upper town, at the foot of the tchink. Again roughly rectangular in shape and

with rounded corners it is roughly 780 metres long and 480 metres from north to south. To the south west of the lower town on the opposite side of the

river channel is the rectangular grid of a sizeable former park or formal garden.

History of Devkesken and Vazir

Thanks to the work of Bizhanov we know that Devkesken was first settled in the 4th to the 3rd centuries BC. The upper fortified town was constructed

with its western side defended by the tchink and its three other sides by double walls built of mud brick on a paqsa foundation.

The walls had regularly spaced rectangular towers along the flanks, square towers at the two corners and an entrance barbican. The space between the

walls contained two galleries - a lower gallery which was windowless with no loopholes and an upper gallery with loopholes for archers in the walls and

in the towers.

Some 15km north of Devkesken lays another remarkable ruin of the same name – a 2½ km-long defensive wall running from one side of the Ustyurt

peninsula to the other, with small fortlets at each end positioned on the edge of the tchink. This too was constructed during the 4th to the

3rd centuries BC and was clearly designed to protect the Khorezm oasis from the nomadic occupants of the Ustyurt plateau.

At some later period the loopholes in the defensive wall at the town of Devkesken were filled in and the towers were bricked up. New outer walls were

added to the northern and eastern sides and new semicircular towers were built along the northern flank. Then at the end of the 3rd or the beginning

of the 4th century AD, the town fell into decay.

The precise reasons for the abandonment of Devkesken are unknown. However this was a time of both environmental and social change. The climate had

entered a phase of aridity, river levels were low and by 400 AD the Aral Sea had contracted to such a degree that it had divided into a number of

separate pools (somewhat similar to its status in 2008). Archaeological evidence suggests that the Daudan and Darya Lyk rivers flowing into the

Sarykamysh Lake may have begun to dry out at sometime around the 4th century. At the same time many of the urban centres of Khorezm were facing decline

as people moved into the countryside to work on the large feudal estates controlled by an ever-growing number of powerful landowners.

Towards the end of the 6th century the climate entered a very warm and wet period, warmer than today. During the second half of the 7th century the

town that would later be called Gurganj began to redevelop on the banks of the Darya Lyk. As it grew in power its ruling family began to challenge

the authority of the Khorezmshah in Kath and in 995 its Amir finally gained control over the whole of Khorezm, making Gurganj his capital. By now the

local people had dammed the river, blocking its flow towards Devkesken and the Sarykamysh Lake for the next four centuries. It is possible that the

dam was temporarily damaged or fell into disuse as a result of the Mongol invasion, since the city of Gurganj was flooded after its conquest.

Nevertheless it must have been quickly repaired as the city, renamed by the Mongols Urgench, soon became one of the greatest centres in the Islamic world.

In 1388 the army of Timur set out to crush the Golden Horde, starting with its wealthy province of Khorezm. The walls of Urgench were breached, the

ruling dynasty was massacred, the city emptied and its buildings deliberately destroyed. In one final act of destruction the dam on the river was

breached. The Amu Darya ceased its flow into the Aral Sea and began to flow along the channel of the Darya Lyk, passing Devkesken along the way. The

Aral delta began to dry out, forcing its nomadic population to follow the water and to relocate along the banks of the Darya Lyk.

Although Timur conquered the Golden Horde and Khorezm he did not incorporate them into his empire, leaving them in a state of great instability.

Throughout the 15th century Khorezm was engulfed in turmoil, partly ruled by the Golden Horde, partly ruled by Timurid Khurasan, and partly ruled by

the newly arrived Uzbeks.

In 1431 Abu'l Khayr Khan, the leader of a tribal confederation known as Uzbeks invaded Khorezm, installing his own ruler - Timur Shaykh - a grandson of

Arabshah ibn Pulad with a direct line of descent from Jöchi. He was the first of a new Uzbek dynasty of Khorezmshahs known as the Arabshahids.

Yet he died childless with just a pregnant widow and given the vacuum arising from the absence of a direct heir the Golden Horde seems to have briefly

regained control of the province. During this brief interval, the leader of the Golden Horde, Mustafa Khan, founded the city of Vazir on the site of

Devesken in 1464.

Arabshahid rule was soon re-established under Timur Shaykh's son, Yadigar Khan, and continued under two of Yadigar's sons. It was then interrupted by

another powerful Uzbek leader, Shaybani Khan, who invaded Khorezm in 1505 and imposed his own governor on the province.

The mosque and mausoleum at Devkesken date from the late 15th or the early 16th century.

We know little about Vazir's early history, although the town must have developed fast. The mosque and mausoleums seem to date from the late 15th or

early 16th century. By now the whole region watered by the Darya Lyk seems to have become a thriving agricultural area. There were also two other

large urban settlements in the vicinity of and under the control of Vazir according to the 17th century authors – Adaq or Yangi-Shah and Tersek.

Tolstov speculated whether Adaq might correspond to the site of Aq qala, located below the south-eastern edge of the tchink, while Tersek might

be Shemakha qala the ruins of a large medieval city some 10km away on the eastern flank of the Ustyurt, which like Vazir existed up to the 17th century.

Nearby is Shirvan qala, the site of yet another ruined centre.

In 1510 the Persian Safavid army defeated and killed Shaybani Khan at Merv, proceeding onwards to attack Khorezm. Persian governors were briefly

installed in the four major cities: Khiva, Hazarasp, Urgench, and Vazir. However the Sunni Khorezmian aristocracy greatly resented Persian Shi'ite rule

and two Arabshahid Sultans, Balbars and Ilbars, organised a rebellion in Vazir. The local nobles closed the gates of the city, massacring the Persian

rulers within. The following day Ilbars was proclaimed Khan. Three months later Ilbars Khan captured Urgench and then rallied the other royal princes

for an attack on Khiva and Hazarasp.

Ilbars Khan ruled Khorezm from Vazir until his death in 1517, which sparked what would become a long-running feud between the two families of Ilbars and

Balbars in Vazir and the rest of the Arabshahid family in Urgench. Initially one Khan was raised in Vazir and another in Urgench, although Urgench soon

won out and resumed its role as the capital for the next two decades. Nevertheless the feud continued and thanks to interference from Bukhara, Qal Khan

was enthroned in 1539 and reinstated Vazir as the capital. He was succeeded by his younger brother Aqatay Khan who also ruled from Vazir. Aqatay was

finally killed in 1556 during an attempt to put down a family rebellion at Urgench. His death brought to an end Vazir's brief claim to fame as the

capital of Khorezm.

The princely dispute was resolved with the appointment of Dost Muhammad as Khan, the first leader of Khorezm to choose to rule from Khiva.

It was during Dost Muhammad's brief reign, in 1558, that Vazir was visited by an Elizabethan Englishman and sea captain named Anthony Jenkinson.

Jenkinson had been financed by English entrepreneurs to explore an overland route to China, and was extremely well prepared for his trip with good

knowledge of the route he intended to follow. After arriving on the coast of Mangishlaq he spent three weeks crossing the Ustyurt plateau to reach

Vazir, which he referred to as "Sellizure", a corruption of Shahr-i Vazir (meaning the town of the Vizier). Here he was summoned to meet the "king"

called Azim Khan, a reference to Hajjim Muhammad Khan, one of Dost Muhammad's cousins. The "king" entertained Jenkinson in his castle at the top of

the hill, which Jenkinson describes as very basic, built of earth and not strong, and fed him on wild horsemeat and mares' milk.

Jenkinson recorded that the local people were poor and had little trade or merchandise, although the agricultural lowland to the south of the castle

seemed to be very productive and was being used to grow succulent fruits, including melons (which he refers to as dinie) and sweet watermelons

(karbus). He also astutely observed that the only water available was drawn from the Oxus, [the Amu Darya, now the Darya Lyk], which was in

the process of drying up:

" ... in short time all that land is like to be destroyed, and to become a wilderness for want of water, when the river of Oxus shall fail."

The Amu Darya was in the process of changing its direction of flow – away from Vazir and the Sarykamysh and back towards the Aral Sea. According to

the ruler and writer Abu'l Ghazi Khan, this change took place 30 years before his birth, in other words in 1573, while the 19th century writer Munis

says it happened in 1578.

On leaving Vazir it took Jenkinson a further two days to reach Urgench where he had an audience with Sultan Ali, yet another cousin of Dost Muhammad.

Jenkinson summed up the conflict within the ruling family by noting that although each prince described himself as "king" or Khan:

" ... he is little obeyed saving in his own dominion, and where he dwelleth: for every one will be king of his own portion, and one brother will

seeketh always to destroy another, having no natural love among them, by reason that they are begotten of divers women, and commonly they are the

children of slaves, either Christian or Gentiles, which the father doeth keep as concubines, and every Khan and Sultan hath at least 4 or 5 wives,

besides young maidens and boys, living most viciously: ... ."

Jenkinson never visited Dost Muhammad in Khiva, but shortly after his departure for Bukhara, the latter was overthrown by the governor of Vazir,

Hajjim Muhammad, who chose to rule Khorezm from Urgench.

It was Hajjim's son, Arab Muhammad, who made the final move of the capital to Khiva in 1602. As Jenkinson had correctly predicted, the Darya Lyk was

drying out and the agricultural oasis of Vazir was dying. However it was not until the reign of Anusha Khan (1663-1685) that the remaining residents

of Vazir were relocated to other regions, one group establishing the new town of Vazir, known as Taza Vazir (New Vazir) to the north of Gurlen in the

Khivan oasis.

Google Earth Coordinates

The following reference point (in degrees and digital minutes) will enable you to locate Devkesken qala and Vazir on Google Earth, although the quality

of the coverage of this region is quite poor:

| | Google Earth Coordinates |

|---|

| Place | Latitude North | Longitude East |

|---|

| Devkesken qala | 42º 17.230 | 58º 23.750 |

| Vazir Upper Town | 42º 17.325 | 58º 23.990 |

| Vazir Rabad | 42º 17.482 | 58º 24.035 |

| Vazir Outer Rabad | 42º 17.581 | 58º 23.230 |

| Vazir Lower Town | 42º 17.163 | 58º 24.030 |

| | | |

Note that these are not GPS measurements taken on the ground.

Visit our sister site www.qaraqalpaq.com, which uses the correct transliteration, Qaraqalpaq, rather than the

Russian transliteration, Karakalpak.

Return to top of page

Home Page

|

|