|

Contents

Visiting the qalas

Recommended Itineraries

Useful Maps

Google Earth Coordinates

A Short History of Khorezm

Visiting the qalas

One of the highlights of any tour of Karakalpakstan is a visit to some of the country's ancient historical monuments. Many of these are dramatically

located in the barren desert wilderness that surrounds the settled agricultural oases where people live today. We are always amazed and disappointed

that tourists flock like sheep to the over-restored cities of Samarkand, Bukhara, and Khiva, yet bypass the far more genuine and ancient monuments of

Karakalpakstan.

If you have made the effort to get as far west as Khiva it would be crazy to miss out on some of the most precious antiquities in the region.

A painting of Ayaz qala 1 and 2.

From the frontispiece of "Ancient Khorezm", by Sergey Tolstov, Moscow, 1948.

In fact the richest district for finding qalas is just on the other side of the Amu Darya from Khiva - in the southern right-bank tumans

or provinces of Biruniy, To'rtku'l, and Ellikqala. Ellikqala is particularly proud of its ancient heritage – its name means "fifty qalas" in Karakalpak.

This tuman is the location of the "must-see" site of Ayaz qala, not one but actually three separate neighbouring sites located in a spectacular

setting to the east of the Sultan Uvays Dag mountain range.

The early Amu Darya did not drain into the Aral Sea but into the Sarykamysh depression, located on the south-western border of Karakalpakstan. From

there it flowed via the river Uzboy into the Caspian Sea. During the second millennium BC the Amu Darya changed direction, flowing to the east of the

Sultan Uvays Dag and thence into the Aral Sea. This eastern channel is known as the Akcha Darya and it watered an oasis that became increasingly

populated towards the end of the first millennium BC and into the first millennium AD. However by the end of the 9th century AD the Amu Darya had

changed direction once again, still flowing into the Aral Sea but now via a north-westerly route. The Akcha Darya was left high and dry and its

population forced to move. Consequently the monuments dating from that intervening period are now located in the desert well away from the modern

centres of population.

There are also many other historical sites in the northern part of Karakalpakstan, although many of these date from a later period. Some are quite

difficult to reach. The most well-known site close to No'kis is Mizdahkan and this can easily be reached from the city in less than an hour.

Just beyond Mizdahkan lie the ruins of Old Urgench, the former capital city of Khorezm for a period of over 600 years. Today it is on the Turkmenistan

side of the border, which is difficult to cross as a day tripper even with the appropriate visas. However if you are planning a circular trip around

Central Asia we recommend that you enter Turkmenistan by road from Karakalpakstan and visit Old Urgench before continuing on to Ashgabat, either directly

by road across the Qara Qum or by taking a domestic flight from Dashoguz.

Recommended Itineries

Obviously the itinerary that you follow is dictated by the time that you have available. Although many of the qalas can be visited as day trips

from either Khiva or No’kis we thoroughly recommend spending longer so that you can see a larger number of sites including those in the more

remote locations.

For those with only a short time available the Biruniy region can be visited as part of a day trip from Khiva or No’kis, although with a journey

time of about two hours each way you will only have time to visit a handful of qalas. There are no buses that pass the qalas so you

will have to hire a car and driver. In Khiva tours can be arranged through many of the hotels, the Juma Mosque, or at the Tourist Information Office

(opposite the Kalta Minor minaret). Tours from No’kis can be arranged through the Savitsky Museum,

Ayimtour at the Jipek Joli Hotel, or a local travel agent

such as Bes Qala Nukus.

If taking a day trip we recommend that you first pay a quick visit to Qızıl qala before

going on to the important but somewhat weather-worn site of Topraq qala . Topraq qala sits in a

dramatic position below the Sultan Uvays Dag but somehow lacks the grandeur of the more remote qalas. It also tends to be a bit busier.

Now head for Ayaz qala, the jewel in the crown. It is not one site but three: a 4th century BC hilltop

refuge known as Ayaz qala 1; the 8th century AD fortified manor house of a feudal lord known as Ayaz qala 2; and a 2nd century AD fortified town

known as Ayaz qala 3. To really experience the site you need to walk up to the top of Ayaz qala 1, from where you get spectacular views of the

other two sites. From Ayaz qala it is not far by car to see Big Qırq Qız qala

and Qurgashin qala. It should be possible to have lunch at the Ayaz qala Yurt Camp provided you

book ahead of your visit.

|

The 4th to 3rd century BC hilltop refuge of Ayaz qala 1 on the right

and the fortified residence of a feudal lord on the left dating from the late 7th to early 8th century AD .

If you have more time available we strongly advise you to visit more of the sites in this region at a more relaxed pace, either on the way from Khiva

to No'kis or vice versa, spending one or preferably two nights at the Ayaz qala Yurt Camp in between.

This is a spectacular location to stay, offering the chance to walk up to Ayaz qala 1 before breakfast or to go and visit the nearby qalas at

sunrise and sunset, the most magical time for viewing or photography. The Yurt Camp is run by a Karakalpak woman (although most of the yurts are Qazaq)

who with the rest of her team takes every effort to make her guests comfortable and to feed and water them well. There is a separate toilet and hot

shower facility, a plentiful supply of beer, wine, and vodka, and often local musicians and dancers to entertain. You can either eat outside in the

starlight (taking care to apply mosquito repellent beforehand) or in the cosiness of your yurt. However to stay there you must make an advance

booking through your local agent.

On the day of your arrival begin at Qızıl qala before moving on to Topraq qala and then drive to the Yurt Camp for lunch (this needs to

be booked at the time of your reservation). In the afternoon walk up to explore Ayaz qala 1 and get good views of Ayaz qalas 2 and 3. Then take a drive

to visit Big Qırq Qız qala and Qurgashin qala, timing your return for just before sunset.

|

The early medieval feudal fort of Ayaz qala 2 as seen from the edge of Ayaz qala 1.

On the second day your priority should be to visit the wonderfully remote site of Janbas qala, but this is

best visited in the afternoon when the front of the site is no longer in shade. In the morning head for

Gu'ldu'rsin qala, 18km south of Bostan, and then take a quick look at

Angka qala, which is on the left hand side of the road as you drive north-west towards Janbas.

If you stay at the Yurt Camp for a second night you can leave after breakfast and head towards No'kis, visiting some of the monuments located along the

Amu Darya on the way - the Sultan Bobo mausoleum and cemetery,

Janpıq qala, southern Gyaur qala, and

Shılpıq. Even if you leave the previous day after visiting Janbas qala you will still have time

to see at least one of these sites along with Shılpıq, which is almost impossible to miss and very easy to visit. Out of all four sites

Janpıq qala is by far the most interesting but unfortunately the least easy to get too.

|

The imposing citadel within the walled city of Janpıq qala.

Once you are in No'kis it is less than one hours drive to the huge necropolis of Mizdahkan and the

adjacent site of the northern Gyaur qala fortress. The nicely located Karakalpak necropolis of Qırantaw

is also easily accessible from No'kis in about an hour.

No'kis is also a good starting point for a visit to a number of important historical sites just across the border in Turkmenistan. Unfortunately in the

madhouse world of modern Central Asia what was once a short and simple trip now requires a Turkmen visa and an encounter with bureaucratic Uzbek

and Turkmen immigration and customs officials which, if you are unlucky, could take up a significant portion of your day. You also need to arrange

separate transport on the Turkmen side of the border, making it almost impossible to cross and return on a day trip.

If you are visiting Karakalpakstan as part of a general tour of Central Asia and want to visit northern Turkmenistan we recommend that you plan a

circular itinerary. Starting in Tashkent make your way to No’kis via Samarkand, Bukhara, and Khiva. From No'kis cross into Turkmenistan at the

Xojeli - Kunya Urgench border checkpoint and arrange for your Turkmen driver to meet you at the border and to show you the local sites. Then

continue to Ashgabat by plane from Dashoguz or by car across the empty Qara Qum. Try to plan to be in Ashgabat for the famous Sunday bazaar.

Visit the archaeological site at Merv, crossing back into Uzbekistan at Turkmenabat and completing the circle back in Bukhara.

The one "must see" site on the Turkmen side of the border is the Kunya Urgench Archaeological Park,

the remains of the Golden Horde city of Urgench, which was destroyed by Timur (Tamerlane) in 1388 along with the rest of Khorezm. Some of the

buildings still standing may date from the 12th century, prior to the earlier successful siege of Gurganj by Chinggis Khan and his four sons.

There are many more archaeological sites on this side of the border. If you have time before your flight we also recommend a quick visit

to Zamakhshah, which is not far from Dashoguz airport.

Useful Maps

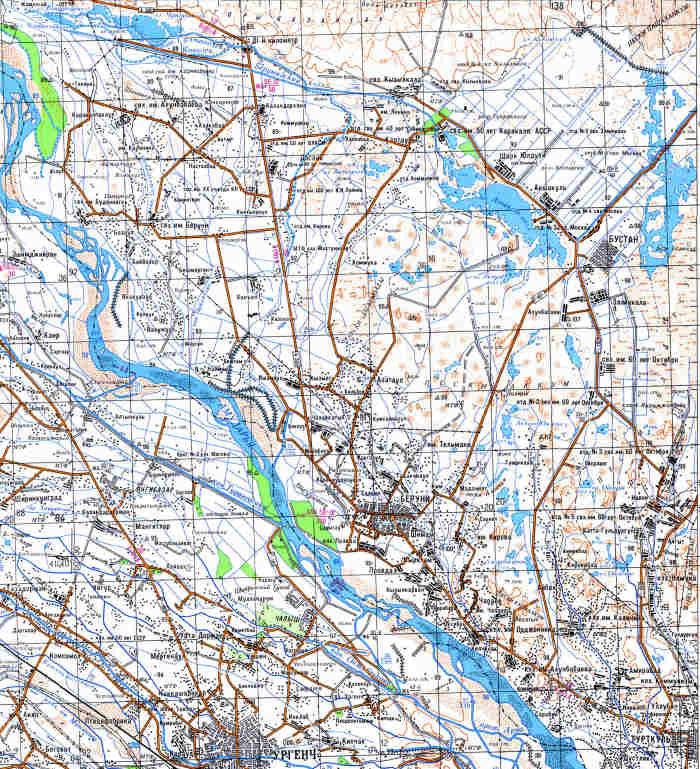

The region with the densest concentration of qalas - the southern part of Karakalpakstan on the right bank of the Amu Darya - is also the

most difficult to navigate within. Roads fan out northwards into the region from Biruniy and To'rtku'l but there are few interconnecting links.

Unless you have a knowledgeable driver, a good map is indispensable.

There is only one set of maps identifying the location of each of the qalas and showing how to reach them by road - the very detailed

1;100,000 Soviet military map series. The full set of 307 maps covering the whole of Karakalpakstan and the rest of Uzbekistan is now available

on-line in digital format, along with 110 of the associated 1:200,000 scale series, for the very modest sum of $35. Contact

mapstor.com. Although these maps were last updated

in 1989, the road system is still basically the same.

|

Topraq qala on the 1:100,000 Soviet map, sheet number K41-074.

The sheet that covers the prime region north of Biruniy is K41-074, while K41-075 includes Janbas qala and Qoy Qırılg'an qala. Ayaz

qala appears on the very bottom of K41-063.

The 1:200,000 series is more practical for driving around but sadly does not mark the majority of the qalas. The key sheet covering the

region north of Biruniy is K41-19.

The region north of Biruniy covered by the 1:200,000 Soviet map K41-19.

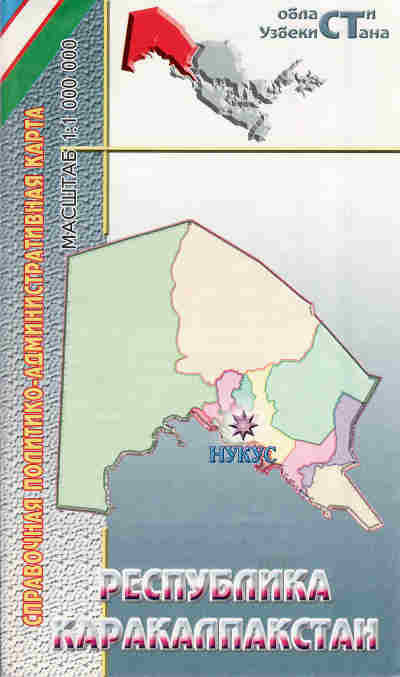

The best relatively up-to-date road map of the Republic of Karakalpakstan is the much bigger scale 1:1,000,000 (10km per cm) map published by

"Kartografiy" Uzgeodezkadastra in 2004 and available from booksellers in Tashkent for a few dollars. It was made in 2002-2003 but is not

particularily good for the most important region to the north of Biruniy.

The "Kartografiy" Uzgeodezkadastra map of Karakalpakstan.

The more detailed 1:400,000 sister map, covering the neighbouring Khorezm Oblast or viloyati, also includes the To'rtku'l, Ellikqala,

and Biruniy tuman of Karakalpakstan. This is the best up-to-date road map for this particular region. Even so it irritatingly does not mark

any of the major archaeological sites in the region.

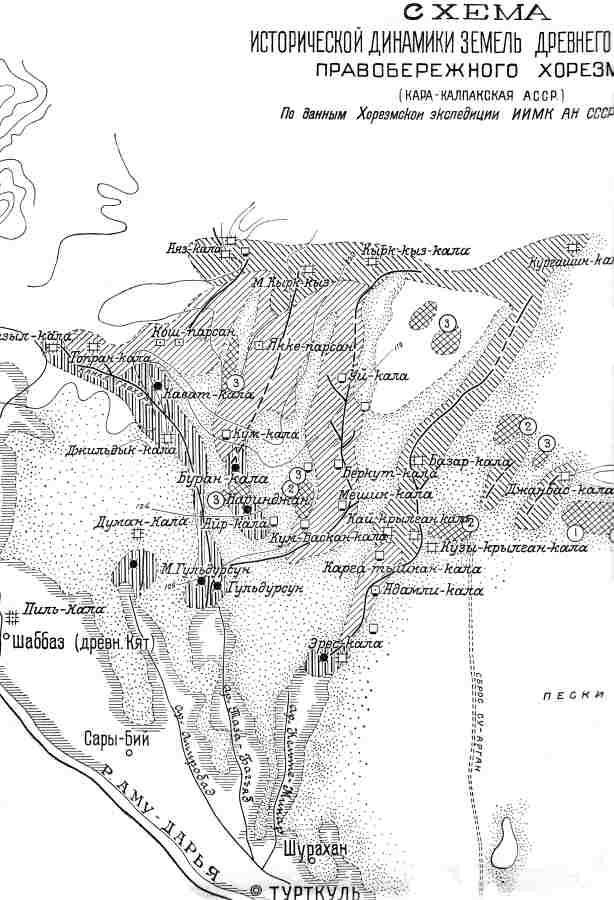

For those just wanting a rough idea of where they and the sites that they are visiting are then a map published by Professor Sergey Tolstov, the

Director of the famous Khorezm Archaeological-Ethnographical Expedition may be sufficient. The map is in Russian and does not show any roads but it

does indicate the relative position of the most important sites. Note that Shabbaz is the modern town of Biruniy. To download a better quality copy

click here.

Map of the qalas in Russian from Tolstov's "Ancient Khorezm", 1948.

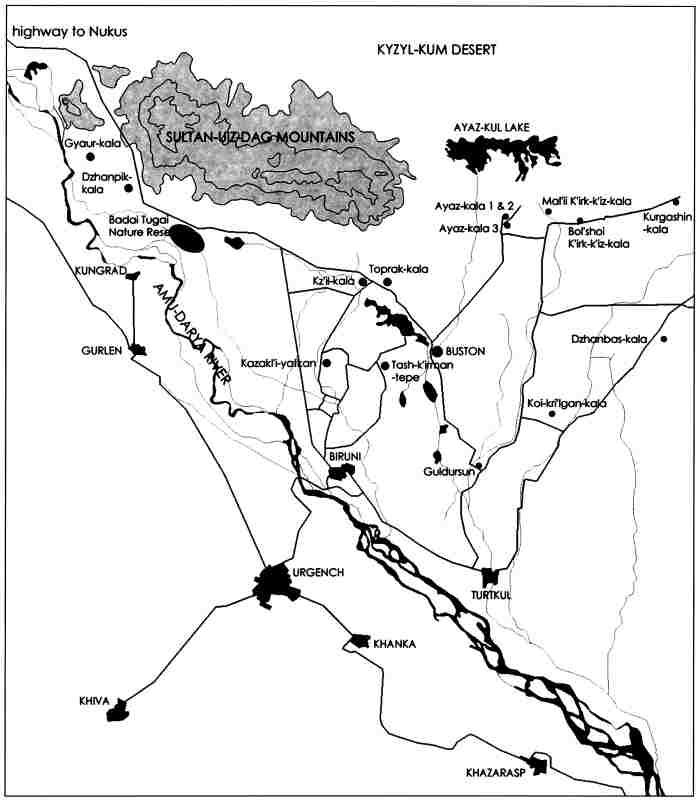

A more up-to-date map was published by Professor Vadim Yagodin and Associate Professor Alison Betts in a small UNESCO booklet titled "Ancient Khorezm"

in 2006. It has now gone out of print but we still recommend that you purchase a copy if you can find one. Professor Betts has kindly given us

permission to reproduce the map below. To download a better quality copy click here.

Map of the main archaeological sites in southern Karakalpakstan.

Reproduced with the kind permission of Associate Professor A. V. G. Betts, University of Sydney.

Although completely impractical for on-the-spot navigation, the best way to familiarize oneself with the location of the main qalas is to

identify their position on Google Earth.

Google Earth Coordinates

Karakalpakstan is particularly well served by Google Earth, with the exception of Shomanay and Taxta Ko'pir. Although coverage of Turkmenistan is

patchy, at least the major site of Urgench can be seen well.

To help with the planning of your trip, the following reference points (in degrees and digital minutes) will enable you to locate each of the

following places. Note that these coordinates come from Google Earth and are not GPS measurements taken on the ground:

| | Google Earth Coordinates |

|---|

| Place | Longitude North | Latitude East |

|---|

| Ayaz qala 1 | 42º 0.854 | 61º 1.746 |

| Ayaz qala 2 | 42º 0.654 | 61º 1.630 |

| Ayaz qala 3 | 42º 0.320 | 61º 1.830 |

| | | |

| Little Qırq Qız qala | 42º 1.090 | 61º 6.075 |

| Big Qırq Qız qala (approximately) | 42º 0.450 | 61º 9.470 |

| | | |

| Qurgashin qala | 42º 2.040 | 61º 19.340 |

| | | |

| Topraq qala 1 | 41º 55.630 | 60º 49.385 |

| Topraq qala 2 | 41º 55.830 | 60º 49.155 |

| | | |

| Qızıl qala | 41º 55.807 | 60º 47.050 |

| | | |

| Yakke Parsan | 41º 55.270 | 61º 1.105 |

| | | |

| Kazakl'i-yatkan | 41º 49.720 | 60º 43.050 |

| | | |

| Pil qala | 41º 42.300 | 60º 44.250 |

| Kath | 41º 40.918 | 60º 43.568 |

| | | |

| Big Gu'ldu'rsin qala | 41º 41.590 | 60º 58.890 |

| | | |

| Angka qala | 41º 45.500 | 61º 9.095 |

| | | |

| Janbas qala | 41º 51.480 | 61º 18.245 |

| | | |

| Bazar qala | 41º 49.460 | 61º 11.230 |

| | | |

| Qoy Qırılg'an qala | 41º 45.317 | 61º 7.020 |

| Adamli qala | 41º 44.450 | 61º 7.338 |

| | | |

| Sultan Uvays Bobo Mausoleum | 41º 0.668 | 60º 38.726 |

| | | |

| Janpıq qala | 42º 1.605 | 60º 19.590 |

| Gyaur qala | 42º 4.840 | 60º 16.555 |

| Shılpıq | 42º 15.840 | 60º 4.180 |

| | | |

| Mizdahkan | 42º 24.070 | 59º 23.360 |

| Gyaur qala | 42º 23.576 | 59º 22.623 |

| Mizdahkan City | 42º 24.018 | 59º 22.960 |

| Muzlum-Khan Sulu Mausoleum | 42º 24.163 | 59º 23.294 |

| Caliph Erezhep Mausoleum | 42º 24.088 | 59º 23.251 |

| Mazar of Shamun Nabi | 42º 24.093 | 59º 23.330 |

| Djumarat Khassab Mound | 42º 24.105 | 59º 23.387 |

| | | |

| Qalmaq qala | 42º 38.660 | 59º 19.290 |

| Qırantaw Entrance | 42º 38.345 | 59º 19.460 |

| | | |

| Kunya Urgench Archaeological Park | 42º 18.647 | 59º 8.247 |

| Tura beg Khanum Mausoleum | 42º 18.674 | 59º 8.231 |

| Seyit Akhmet Mausoleum | 42º 18.589 | 59º 8.356 |

| Qutlugh Timur Minaret | 42º 18.521 | 59º 8.515 |

| Sultan Tekesh Mausoleum | 42º 18.445 | 59º 8.633 |

| Kyrk Molla Hill | 42º 18.516 | 59º 8.767 |

| Mausoleum of Fakhr ad-Din Razi | 42º 18.269 | 59º 8.739 |

| The Ma'mun Minaret | 42º 18.120 | 59º 8.738 |

| Gate of the Caravanserai | 42º 17.864 | 59º 8.728 |

| Aq qala | 42º 17.785 | 59º 9.125 |

| Khorezm Bag | 42º 17.839 | 59º 7.917 |

| | | |

| Najm ad-Din Kubra Mausoleum | 42º 19.545 | 59º 8.762 |

| Sultan Ali Mausoleum | 42º 19.564 | 59º 8.768 |

| | | |

| Zamakhshar | 41º 43.900 | 59º 43.100 |

| | | |

| Devkesken qala | 42º 17.230 | 58º 23.750 |

| Vazir Upper Town | 42º 17.325 | 58º 23.990 |

| Vazir Rabad | 42º 17.482 | 58º 24.035 |

| Vazir Outer Rabad | 42º 17.581 | 58º 23.230 |

| Vazir Lower Town | 42º 17.163 | 58º 24.030 |

| | | |

| Kalali Gyr 2 | 41º 48.300 | 59º 3.210 |

| | | |

| | | |

Beware about the labelling of certain locations in Karakalpakstan and Turkmenistan shown on Google Earth! Some are properly labelled, but many are

erroneously or mischieviously not.

A Short History of Khorezm

In the modern guidebooks Khorezm is portrayed as little more than the smallest province or viloyat of Uzbekistan, with its administrative

centre at Urgench and its main tourist centre at Khiva.

However for most of the past two and a half thousand years Khorezm (sometimes called Khorezmia or Chorasmia) has been a nation state with its own

unique civilization and culture, occupying the lands watered by the lower reaches of the Amu Darya. Most people throughout the Western world have

never heard about the Khorezmians. Our classical education encompasses the Greeks, the Romans, and even the Persians, but seems strangely myopic about

the contemporary civilizations of Central Asia.

Khorezm has always been remote, isolated by the barren Ustyurt Plateau to the west, the Aral Sea to the north, the Qizil Qum to the east, and the Qara

Qum to the south. The valley of the Amu Darya still remains the main route into and out of the region. Surrounding powers have frequently attempted

to exert their authority over the province, but its isolation has made it difficult to control from afar. Over time it has always re-established its

independence.

Just as the existence of Egypt depends solely on the Nile, so Khorezm depends completely on the Amu Darya. However the Amu Darya carries huge amounts

of silt down from the high Pamirs, which slowly choke up its lower channels. In the past its rapid flow during the spring and summer flood seasons

gave it a power that far exceeded the resistance of its compacted banks of alluvial sand. As a result it gained the reputation as the "mad river",

continually changing its course over time. As the flow of the river has switched from the west, to the east, and to the north, so the agricultural

communities that have settled along its banks have been forced to move. Consequently the geographical shape of Khorezm has continually changed over

time. The history of Khorezm is very much a history of the lower Amu Darya.

There are signs of human habitation in the Aral region over much of the past one million years. Late Palaeolithic sites around former shorelines of

the Aral Sea suggest that this body of water was already in existence before the last Ice Age. As the ice sheets retreated into the high Pamirs and

Tien Shan much of the region seems to have remained virtually uninhabited. However with the onset of major climate change in the 7th or 6th

millennium BC, Neolithic hunter-gatherers arrived on the surrounding steppes, exploiting the huge herds of migrating antelope and deer as well as the

rivers and lakes teeming with fish and wildfowl.

At this time the Amu Darya flowed westwards into the Sarykamysh Lake and then south to drain into the southern Caspian Sea. Later in the 2nd

millennium BC it changed direction, flowing north towards the Aral Sea on a route than ran east of the Sultan Uvays Dag mountains. This channel was

known as the Akcha Darya and nomadic livestock-breeders migrated into the region and settled along its banks. Some of them probably believed in a

primitive cult of fire worship.

The founding of Khorezm still remains a major mystery. At some time in the late 7th or early 6th century BC, a tribe of cattle-breeders moved into

the old Sarykamysh delta. They were Sakas: horse-riding nomads with wheeled carts, iron weapons, the compound bow, and a sophisticated material culture.

Thankfully they left behind the remains of their kurgan burials along with the ruins of a defensive fort and tribal capital known as Kyuzeli Gyr,

located on a low hill just across the border in northern Turkmenistan. It was little more than a walled refuge for the nomads and their livestock, and

some have suggested that it may have been the origin of the word Khorezm – in the Aramic language of the Avesta a "var" was a refuge or place

of protection so "var zamin" would have been the "land of good refuge".

At the same time a quite different group of people seem to have been migrating north into the lower reaches of the Amu Darya. These were descendants

of the much earlier Oxus Civilization of eastern Turkmenistan and southern Tajikistan and they imported new technologies into the region: construction

using compacted clay and unbaked bricks, pottery making using the wheel, and farming using advanced methods of irrigation. The remains of their early

settlements lie below the watertable along the banks of the Amu Darya, and while a few have been excavated many more have been lost to posterity.

In the mid-6th century BC these two peoples were conquered by the Persians and seem to have been forged into a single state. Khorezm became a province

or satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire, forced to pay tribute and to provide troops to fight in the Persian wars against the Greeks. It also shared

similar Zoroastrian beliefs. However as the Achaemenids became locked into their protracted war with Greece, Khorezm gained its independence –

possibly in the early 4th century BC. Freed from the financial burden imposed by Persia it enjoyed a period of rapid agricultural and economic

development. Its political centre was moved from the left bank to a new capital on the right bank, known today as Kazakl'i-yatkan. To protect the

agricultural oasis from nomadic attack a string of defensive forts were built along its northern and eastern frontiers, usually positioned on natural

elevations. Examples include Janbas qala, Ayaz qala 1, Big Qırq Qız qala, and Qurgashin qala. Gyaur qala was built close to the Amu Darya

to protect the river route from the south.

In 334 BC a vengeful Alexander the Great set out with his Macedonian army to crush the remains of the Achaemenid Empire. After conquering Persia he

set out to destroy its colonies in Central Asia and although his army never got close to Khorezm, the Khorezmshah did send an embassy to meet Alexander

at Marakanda (Samarkand).

Towards the end of the 2nd century BC warlike nomadic tribes from China and western Mongolia took control of Sogdia and Bactria. They soon extended

their rule as far as the Indus, creating the foundations of the Kushan Empire. The Kushans propagated Buddhism in all of the territories that they

conquered and the absence of a Buddhist culture in Khorezm at that time suggests that it preserved its independence. The Kushan period was a time of

stability, agricultural expansion, increasing trade, and of cultural renaissance. In the 1st century AD or a little later the rulers of Khorezm

constructed a magnificent summer palace at Topraq qala. The right bank region surrounding Shılpıq had already become a royal sanctuary,

reserved for the Zoroastrian funeral ceremonies of the ruling dynasty.

In the 3rd century AD Kushan power was eclipsed by the rise of Sasanian Iran, which may have exerted power over Khorezm for a brief period. By now

major economic and other changes were underway. Land was becoming increasingly concentrated in the hands of feudal lords, or dihqans,

descendants of the ancient nobility. The dihqans constructed small feudal forts such as Yakke Parsan and Teshik qala from which they could

manage and rule their rural estates known as rustaq. As economic wealth moved into the countryside so the main urban centres went into

decline. Climate change might have also played a part, with the outer agricultural regions contracting, especially on the left bank of the Amu Darya.

The former capital was abandoned and moved south to Al-Fir on the outskirts of modern Biruniy, today known as Pil qala. In time it developed into a

major city called Kath. Social changes were also underway, driven by waves of new immigrant nomads from the east, beginning with the Huns and

continuing with the early Turks. Khorezm successfully absorbed these new cultures without losing its Zoroastrian roots.

In the mid-7th century the recently unified Arabs established an important colony at Merv and began to send raiding parties into Khorezm. It was not

until 712 that the Arab army finally took control, invited into the province by a desperate Khorezmshah in Kath who had lost control of his territories

on the northern left bank. However the Arab colonists were Islamic zealots who forcibly extinguished the Zoroastrian faith. An Arab governor was

installed in the newly emerging town of Gurganj tasked with raising taxes for the caliph and for actively promoting Islam.

During the 8th century the urban centres of Khorezm began to intensively adopt Arab customs, although it would take more than half a millennium to

convert the surrounding nomads. The Khorezmian elite became increasingly linked culturally and economically into the wider Islamic world. Meanwhile

in the surrounding steppes a new nomadic federation called the Pechenegs was forming, incorporating many tribes from the Syr Darya such as the Kanga,

Keneges, and Bashkirs. They were quickly followed by the arrival of the Oghuz Turks, who entered the Syr Darya valley from the Tien Shan and violently

pushed the Pechenegs westwards towards the Volga and beyond.

Towards the end of the 9th century the Samanid dynasty, which had earlier gained power in Samarkand and Bukhara, took control of Khorezm and Khurasan.

The Samanids created a strong, partly centralized, partly federal state that shielded Khorezm from incursions from the steppes for virtually the whole

of the 10th century, resulting in an era of stability and economic growth. However the thriving capital of Kath was increasingly being flooded by the

Amu Darya, while the northern city of Gurganj and its surrounding hinterland had become sufficiently powerful to refuse to acknowledge the authority

of the Khorezmshah in Kath. It may have been during this period that the port of Janpıq qala was established on the Amu Darya.

As the 10th century reached its close the Samanids lost power to the expanding Turkic dynasty of the Qarakhanids. Meanwhile the internal schism within

Khorezm reached crisis point in 995. The Amir of Gurganj invaded Kath, deposed the Khorezmshah, reunited the country, usurped its throne and relocated

its capital to Gurganj. However his dynasty was extremely short-lived. In just over twenty years his son was deposed by the Ghaznavids, a military

regime based in the modern territory of Afghanistan, who placed their own incumbent on the Khorezmian throne.

Twenty-six years later the Ghaznavids were in turn ousted from Khorezm and Khurasan by the Seljuks, a leading faction of the Oghuz Turks who had

migrated south from the lower Syr Darya during the early 11th century. Khorezm now became a province of Seljuk Khurasan with authority over Khorezm

resting with Anush-tegin, a former slave who had risen through the ranks to become a senior military general. In 1097 Anush-tegin's son, Muhammad, was

appointed Khorezmshah, the first of one of the most successful line of rulers in Khorezm's history – the Anushteginid dynasty of Khorezmshahs.

In the middle of the 11th century the Aral steppes had been overwhelmed by an influx of warlike Turkic nomads known as Qipchaqs. The new Khorezmian

rulers responded by progressively forming alliances with the Qipchaqs and recruiting them as a mercenary army. Although Khorezm continued to acknowledge

the authority of the Seljuks in Khurasan well into the 12th century it was increasingly gaining its independence. However in 1141 Khorezm faced a new

threat, an attack by the Qara Qithay, an aggressive confederation of Mongol tribes that had fled westwards following conflict in Manchuria. Khorezm

continued to pay annual tribute to the Qara Qithay for over 30 years up to the enthronement of the powerful Khorezmshah Tekesh in 1172. Tekesh not only

resisted the Qara Qithay but extended Khorezmian authority over Khurasan, northern Iran, and the Syr Darya. It is possible that one of the major

monumental ruins at Kunya Urgench is Sultan Tekesh's mausoleum.

Khorezm reached its pinnacle of power under Tekesh's son, Ala ad-Din Muhammad, who conquered Transoxiana and annexed much of northern Afghanistan.

By 1220 Muhammad controlled an empire stretching from Baghdad to Tashkent and from the Syr Darya to the Indus Valley. He began to refer to himself as

the "second Alexander of Macedon" and his royal seal bore the expression "The Shadow of God on Earth".

However the massacre of merchants accompanying a caravan from Mongolia at the Khorezmian border town of Otrar in 1215 subsequently escalated into a

major dispute between Sultan Muhammad and his far eastern neighbour Chinggis Khan. At the beginning of 1221 a Mongol army appeared at the gates of

Gurganj, having already conquered Bukhara, Samarkand, and the towns along the Syr Darya. The city fell after a four-month siege and Khorezm became part

of the Mongol Empire, allocated to Chinggis's son Jöchi.

During the 13th century Khorezm re-emerged to become the main commercial, cultural, and religious centre of the Golden Horde, ruled from the Mongol

nomadic capital of Saray on the Volga. Given its strategic location on the main Mongol trading route to the Black Sea ports and Europe, Urgench became

one of the great cities of the Islamic world. Yet once again misfortune struck. In the middle of the 14th century an outbreak of the Black Death at

Saray wreaked havoc on the leadership of the Golden Horde, leading to a period of political instability and infighting.

Meanwhile in 1363 an ambitious young Turkic prince named Timur gained control of Transoxiana. Once firmly in power he began to exert his authority over

the surrounding provinces – East Turkestan, the Syr Darya, Khorezm, and Khurasan. In his attempts to subject Khorezm to his authority he mounted four

military expeditions against the province between 1372 and 1379. When Khorezm finally formed an alliance with the Golden Horde and waged a combined

attack on Transoxiana, Timur organized a devastating counter attack - starting in Khorezm. Urgench was overwhelmed, its ruling family was massacred and

the city was deliberately destroyed, as were many other urban centres throughout Khorezm. Timur's motivation was more than military. He wanted to

eliminate Khorezm as a potential commercial competitor to his own imperial city of Samarkand.

Khorezm was not only finished forever as a major power but soon became a target for attacks from a new nomadic confederation from the north who called

themselves Uzbeks. In 1430 Tash qala, a small walled town built with the permission of Timur on the ruins of Urgench, was sacked by the Uzbek leader

Abu'l Khayr Khan.

The control of Khorezm continued to alternate between Timurid Khurasan and the remnants of the Golden Horde, although by the early 16th century the

Uzbeks were finally in full control. However things were far from stable and the country remained in a state of almost permanent civil war, with members

of the ruling family constantly feuding for power. In 1602 the capital was relocated to Khiva but Khorezm still remained a brigand state for almost

three more centuries, a dangerous place for outsiders to visit or to engage in commerce. There was inter-ethnic strife between the Uzbeks and the

Turkmen and later between the Khivan Uzbeks and the Aral Uzbeks and Karakalpaks, occasionally interupted by incursions from Persia and Bukhara. It was

not until the conquest of Khorezm by the Russians in 1873 that some semblance of order was finally imposed.

Visit our sister site www.qaraqalpaq.com, which uses the correct transliteration, Qaraqalpaq, rather than the

Russian transliteration, Karakalpak.

Return to top of page

Home Page

|

|